Here’s a deal that resulted in 1,500% ROI in five years: in 2018, Staple Street Capital bought a $38.8 million majority stake in a Denver-based tech firm named Dominion Voting Systems. Two years later, certain Republican-leaning media outlets amplified unfounded accusations that the firm’s election machines fraudulently switched votes in the presidential election.

On the eve of a defamation lawsuit, Fox News agreed to pay Dominion a settlement of $787.5 million. Staple Street’s presumed cut of $598.5 million was more than half the value of its total existing portfolio! (Fox News And Dominion Settlement Gives Private Equity Firm 1,500% Return – Bloomberg)

It’s the kind of financial homerun PE dealmakers dream of. But was it factored into the analysis of the Staple Street professionals who engineered the 2018 deal? No way. It was a black swan event, unforecastable by any logical means. And while the Dominion acquisition may have been a smart move in 2018, it’s safe to say that in the absence of the lawsuit and settlement, the deal’s ROI would not have been anywhere near 1,500%.

That brings us to the question of how PE firms generate legitimate returns of the non-black-swan variety. Generally, they come from three sources: increased earnings, the deleveraging process, and higher exit multiples. So let’s discuss these sources in a bit more detail and also dive into how their relative importance has evolved over time and in today’s market environment.

1. Increased Earnings

A primary goal of nearly all private equity deals is to increase earnings for the acquired company. This is sometimes called operational value creation, and can involve cost-cutting, revenue growth or both. Regardless of how they are generated, increased earnings can help drive higher returns in multiple ways. In addition to the direct benefit of higher earnings on exit, they fuel the other two sources of returns by creating cash flow for debt paydown (deleveraging), while also in some cases bringing the business to a new level of scale and/or profitability that can enhance exit multiples.

2. The Deleveraging Process

Archimedes said that with a long enough lever he could move the world. It’s also the case that with enough financial leverage, a PE firm can execute almost any deal, regardless of how much dry powder it has. Anyone who has studied a basic LBO (Value Drivers in an LBO Model | A Simple Model) knows that higher upfront leverage can increase returns as long as the interest rate is lower than the cost of equity capital. To put it another way, leverage allows a small amount of equity to control a large amount of revenue and earnings (examples of leverage creating / destroying value). And as time passes, with healthy cash flow and earnings growth, the PE firm can pay down debt, deleveraging the business to drive returns even higher. But on the front-end of deals, higher leverage also means higher risk, and relying on leverage becomes more difficult when interest rates rise, as they have been recently.

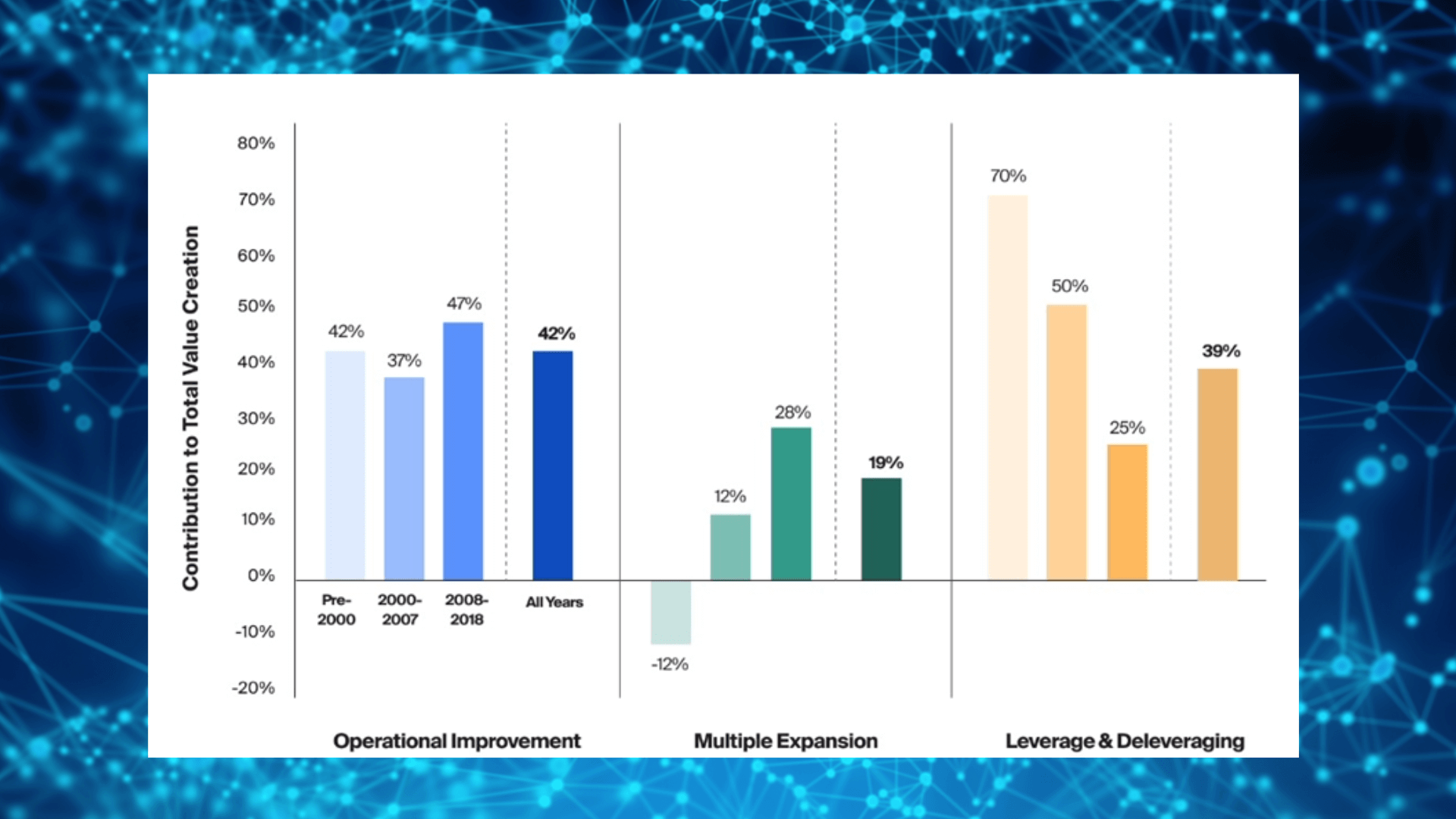

Figure 1 below shows that prior to 2000, the deleveraging process made up a greater share of total value creation (70%) than either operational improvements (42%) or multiple expansion (-12%). But in the chart’s most recent period (2008-2018), its share tumbled to only 25%. Aggregated data from more recent years is not readily available, but my sense is that in the current environment, the share of returns coming from what the chart categorizes as “operational improvement” is growing, at the expense of deleveraging and/or multiple expansion.

Figure 1. PE Value Creation Evolves Over Time (source: Evolving drivers of private equity value creation – CAIS (caisgroup.com))

(Background added)

3. Exit Multiples

Exit multiples can be heavily influenced by factors such as market conditions and interest rates, which are outside the control of both the PE firm and its management partners. In fact, I have called exit multiples the single most difficult-to-predict variable in private equity investing (Private Equity in a Recession | A Simple Model). For this reason, seasoned investors are extremely cautious about forecasting multiple expansion in their upfront investment cases. When I was a young investing newbie, I once expanded an exit multiple in a model without sufficient justification. Let’s just say the partner I reported to was not on board with this aspect of the model, nor shy about letting me know it.

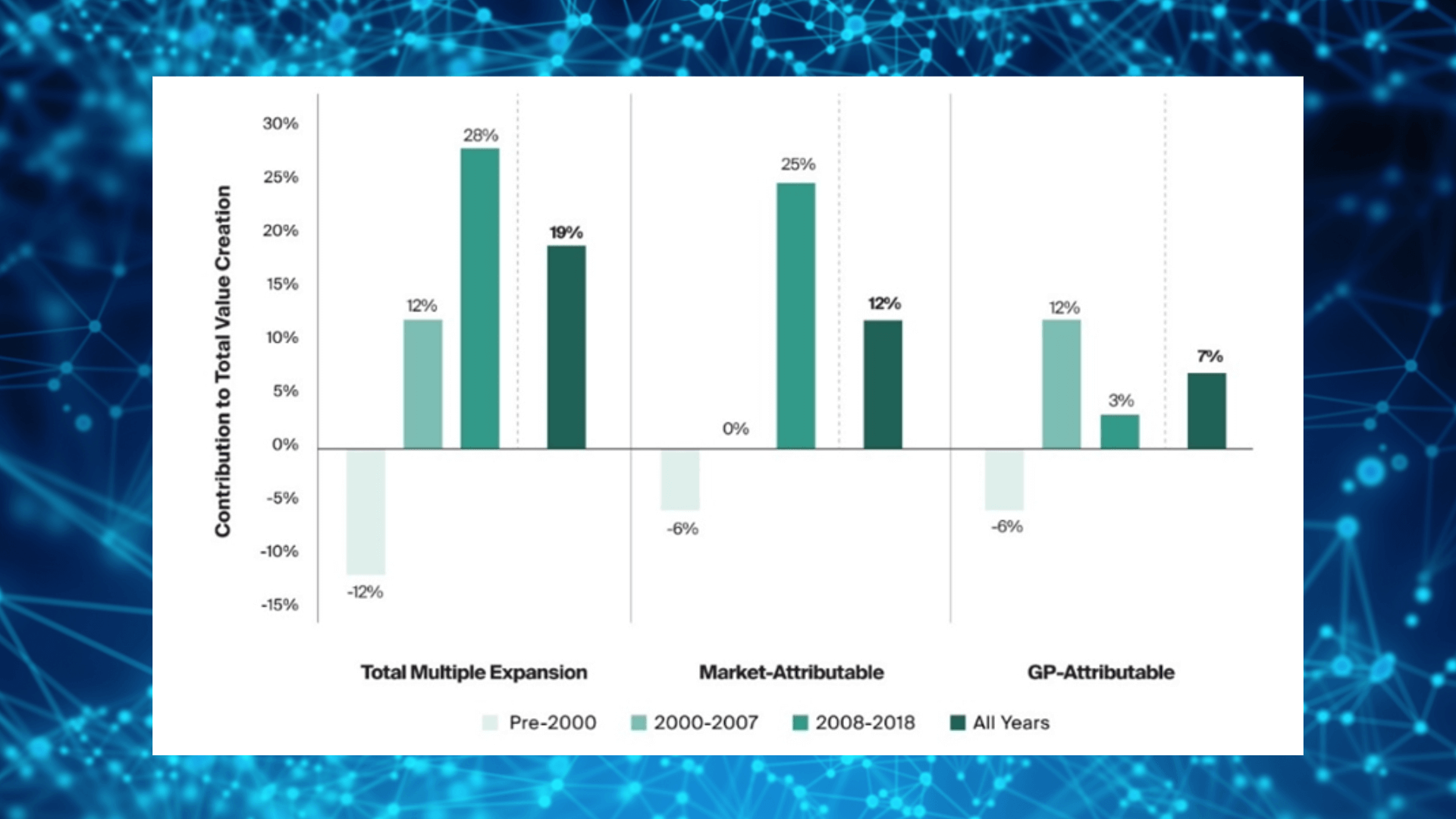

With that said, there are some actions within a firm’s control that in certain cases can grow a company’s multiple over time, such as significantly expanding the scale of the business, increasing the share of high-margin or technology-enabled offerings or diversifying the customer and/or product mix. Figure 2 shows not only how multiple expansion has accounted for a growing share of PE value creation in recent decades (similar to the trends shown in Figure 1), but also what portion of the multiple expansion is attributable to market forces versus GP efforts. To the point above, though, it is worth noting that over time, market forces outweighed GP efforts by a ratio of more than 8:1 in the most recent period.

Figure 2. Multiple Expansion: Market versus Partner Attributable (source: https://www.caisgroup.com/articles/evolving-drivers-of-private-equity-value-creation)

(Background added)

The Role of Holding Periods in Return Creation

The length of time a PE firm plans to hold a business plays a role in how the deal will be expected to generate returns. Private equity has a reputation for moving fast—acquiring targets, implementing a value creation strategy, and selling quickly. This agility is a major advantage PE firms have over public companies and other large strategics that often must clear time-consuming regulatory and bureaucratic hurdles to consolidate.

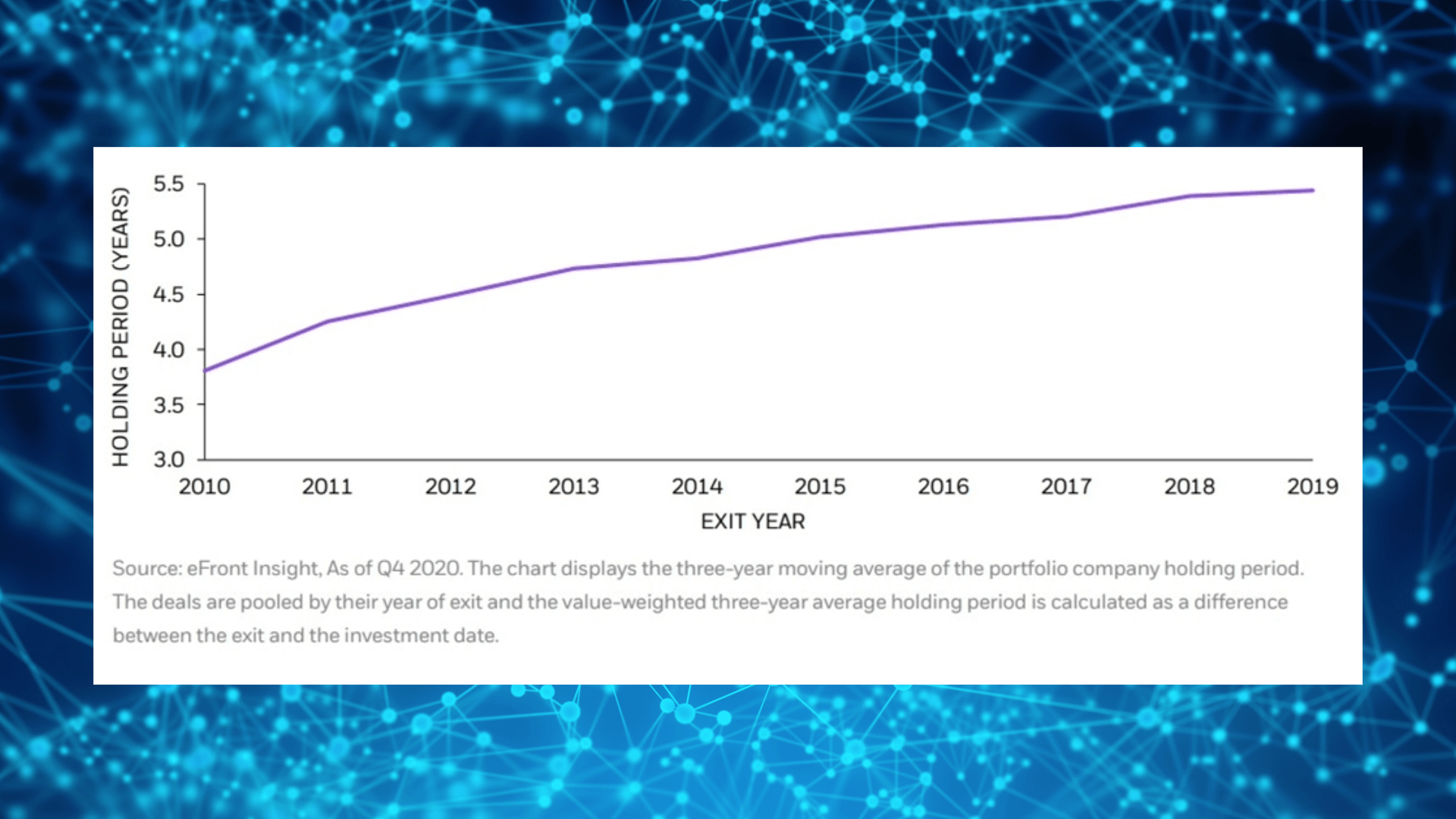

But this is changing. While most PE deals are still financed with loans that must be paid off or re-financed within no more than 5-7 years, holding periods have been creeping steadily up since 2010, as Figure 3 shows. A slowing, uncertain economy may be one reason.

But in many cases, it’s simply an evolving strategic focus. Some fund managers, seeing the potential for further growth in a deleveraged company, will recapitalize it and distribute a cash dividend before starting the deleveraging process anew, especially when exit conditions are not ideal. Additionally, as PE funds have grown and managers are increasingly going after larger and more “professionalized” targets, eking out earnings growth and business improvements may take longer than it did when funds first started acquiring smaller, founder-run businesses decades ago.

Figure 3. Private Equity Holding Periods Are Growing as Capital Becomes More Patient (Source: Exit environment in 2020 and evolution of holding periods | eFront)

(Background added)

Longer holding periods, however, can mean greater interest expense, as well as more uncertain exit multiples if the sale environment evolves in unforeseen ways. This will make the source of returns most under the PE firm’s control—old-fashioned earnings growth—increasingly important as holding periods lengthen.

Conclusion: A Winning Move for Returns

Interest rates will probably remain elevated for the foreseeable future, certainly relative to the cheap money investors have become accustomed to since the Financial Crisis. PE firms need to adapt—modifying or reinventing strategies for generating ROI. Returns will still be there, but they may not come as easily as before. Operational improvements to grow earnings within a fund’s control will be paramount, and firms already focused on this with the infrastructure to match (e.g., stables of operating partners, in-house and cross-portfolio best practice toolkits, etc.) may be at an advantage in the coming years.

There may also be a growing advantage to sourcing companies that have not previously been PE owned, and therefore are more likely to still have ample room for operational refinements. This logic applies not only to PE funds sourcing targets, but also to independent sponsors looking to buy businesses and even executives deciding on a company to settle at in uncertain times. Focusing on businesses with plenty of levers for operational improvement, and having a plan for working them, will likely be a winning move, rather than taking short-term gambles on leverage and market multiple improvements.

Related: Value Drivers in an LBO Model

Learn more about private equity transactions with ASM’s Private Equity Training course. The Private Equity Training course at ASimpleModel.com was developed by industry professionals. The content below goes beyond the LBO model to explain how private equity professionals source, structure and close transactions.