Context: I recently received a question from an entrepreneur in the process of negotiating the sale of a control equity position in his business where he would remain post transaction as CEO and a minority shareholder. Most everything detailed in the offer was clear except for a footnote explaining that IRR’s referenced in the term sheet would be calculated using the =XIRR formula in Excel. This was of particular interest because his ownership had the potential to grow substantially post transaction if the business generated certain “hurdle” IRRs at exit. (As a crude example, imagine that at an IRR of 15% the entrepreneur would be entitled to an additional X number of shares, and at an IRR of 30% an additional 2X shares, etc.)

What perplexed him was that attempts to recreate the IRR schedules in the document generated different outcomes if the =XIRR formula or =IRR formula was used. Why did it differ at all?

Q: Why do =XIRR and =IRR calculate different IRRs in some scenarios?

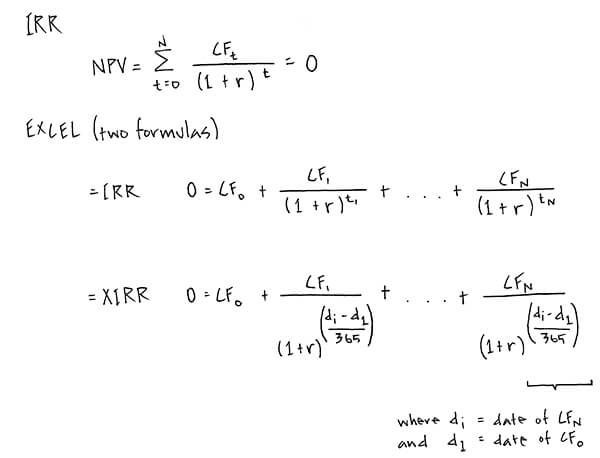

A: It helps to distinguish between the Internal Rate of Return (“IRR”) and the Excel formulas =IRR and =XIRR. The Internal Rate of Return (“IRR”) is the rate (“r”) at which the Net Present Value (“NPV”) of all future cash inflows and outflows (“CF”) for a project is zero.

The Excel formulas, =IRR and =XIRR, are designed to calculate the IRR under different scenarios. What differs between the two formulas is what you are communicating to Excel by selecting one over the other.

With the =IRR formula you are telling Excel to expect equal time periods between cash flows (months, years, etc.), and to calculate the rate of return per period. The =XIRR formula, however, was designed to be more flexible. By using this formula you are communicating to Excel that time periods may be incongruous, and that this needs to be taken into account. It helps to look at the equation behind the formula:

The difference is that “t” (time period) in the =IRR forumla is substituted by the quotient of the difference in days between the first cash flow and a particular cash flow over 365.

So the primary difference between the two is that the =XIRR formula provides some additional flexibility, and has been adjusted to accommodate incongruous time periods. If the =IRR formula is used in any scenario where the time periods between cash flows are not equivalent, it will return an incorrect value. But the =XIRR formula will be correct in both scenarios.

The reason the results differ when measuring the internal rate of return over a number of years is that every fourth year is a leap year. You can test this by building two schedules and measuring the internal rate of return with both the =XIRR and =IRR formula. For years 2017, 2018 and 2019 the results will match, but once 2020 is included you will notice a difference if you include enough decimal places (next leap day: February 29, 2020). The video in the follow up post elaborates on this.

See follow up post: Excel: =IRR() vs. =XIRR() (continued)

See related video: Net Present Value.

Note: This is an abridged overview of the principal difference between the two Excel formulas. The unique characteristics of each could be discussed in much greater detail.

Click HERE to have posts like this one sent directly to your inbox.