Seasonality can have a drastic impact on the amount of working capital required to run a business, which is why it is frequently cited as one of the primary revenue-related challenges in negotiating the working capital adjustment in a private equity transaction (aka “the working capital peg”). To help give this concept some teeth, in this post we will use visuals to explore how seasonality impacts the liquidity required to maintain a business.

To emphasize this point, imagine that you have an opportunity to buy one of two businesses. In this hypothetical scenario, both companies generate $10 million of profit selling 1 million pool floats per year at a price of $30 dollars each. Financially, everything about these two businesses is identical apart from monthly sales volumes and the liquidity required to support these volumes. In other words, the primary discrepancy relates to seasonality.

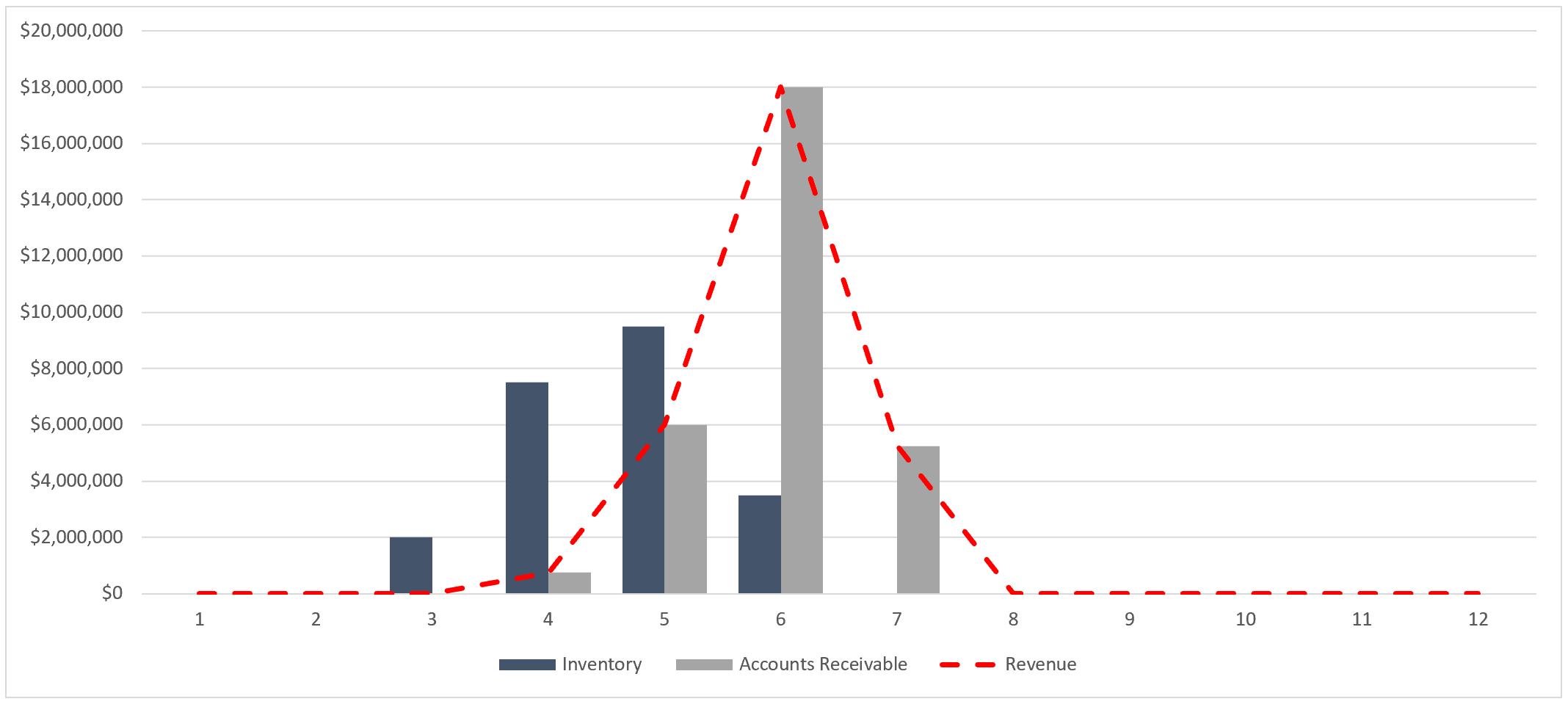

High Seasonality Example

In the first example we will assume that the business is located in Texas, and that all of the company’s customers are also located in Texas. Texas is notoriously hot during the summer months, so it would be practical to assume that the company’s sales ramp in anticipation of the heat and that sales peak sometime in summer (please see chart).

The management team of this company, being fully aware of the company’s revenue cycle, significantly increases inventory purchases early in the year. By June of each year this company has all the inventory it will require for the summer season. During these summer months, sales increase, inventory is sold off and the company generates cash.

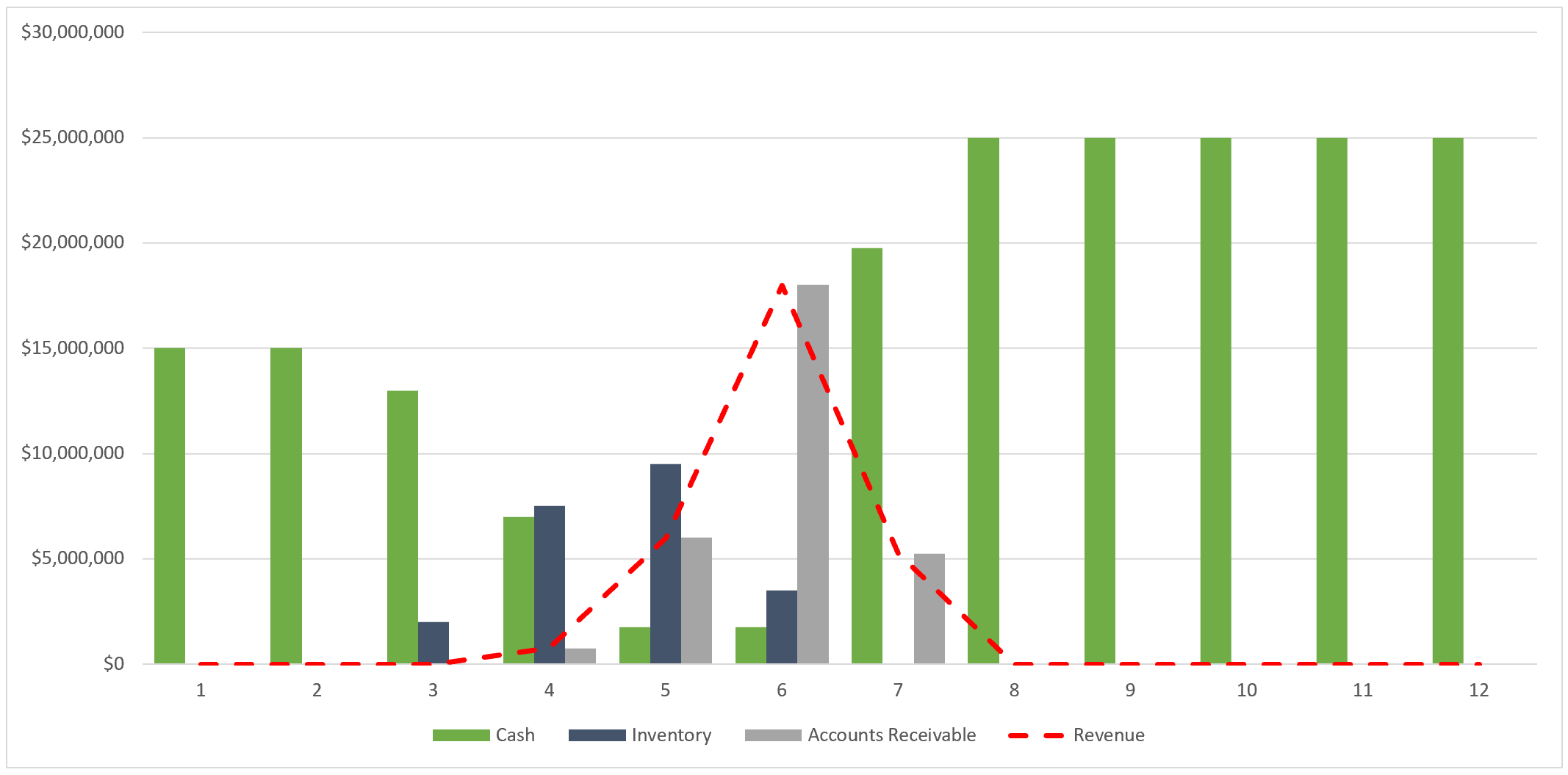

The challenge is that such a ramp in working capital requires cash to accommodate both inventory purchases in advance of sales and the delay of cash receipts from accounts receivable. In the image that follows the chart has been updated to include cash.

From the chart above it is obvious that the company made a profit selling pool floats because it has substantially more cash after the selling season, but what you will also notice is that the company nearly ran out of cash attempting to fund the growth of inventory and accounts receivable. Had sales spiked more abruptly, the $15 million cash balance that the company started the season with would have been insufficient. It is a little counterintuitive, but strong growth can bankrupt a company with positive net working capital.

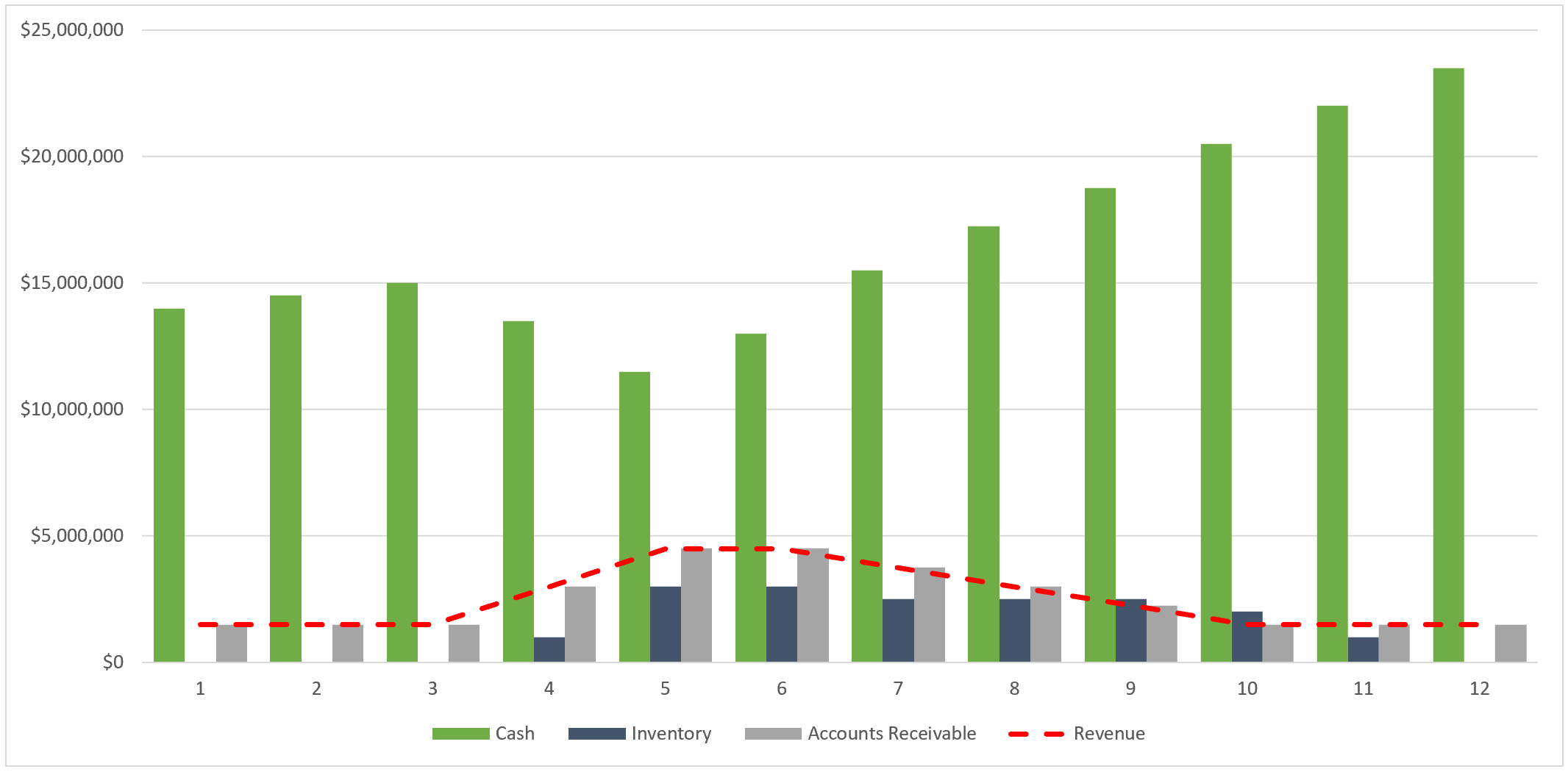

Low Seasonality Example

If you were to take the exact same annual sales but reduce the seasonality, the outcome is wildly different. It is in fact quite obvious from the chart that the amount of cash on the balance sheet is no longer necessary. In this new scenario, with the exact same number of units sold at precisely the same profit as before, cash does not drop below $11 million (please see chart).

The best way I have found to communicate the value of this discrepancy to an entrepreneur or CEO is to ask them to imagine that they own the business in its entirety (some of them already do); and then explain that if they can find a way to reduce seasonality the difference in liquidity can be transferred from the company’s balance sheet to the owner’s bank account.

For more information on the working capital peg in a private equity transaction please see the course titled “Working Capital Adjustment Process“ (Subscriber Content).

Related Video: Introduction to the Working Capital Adjustment