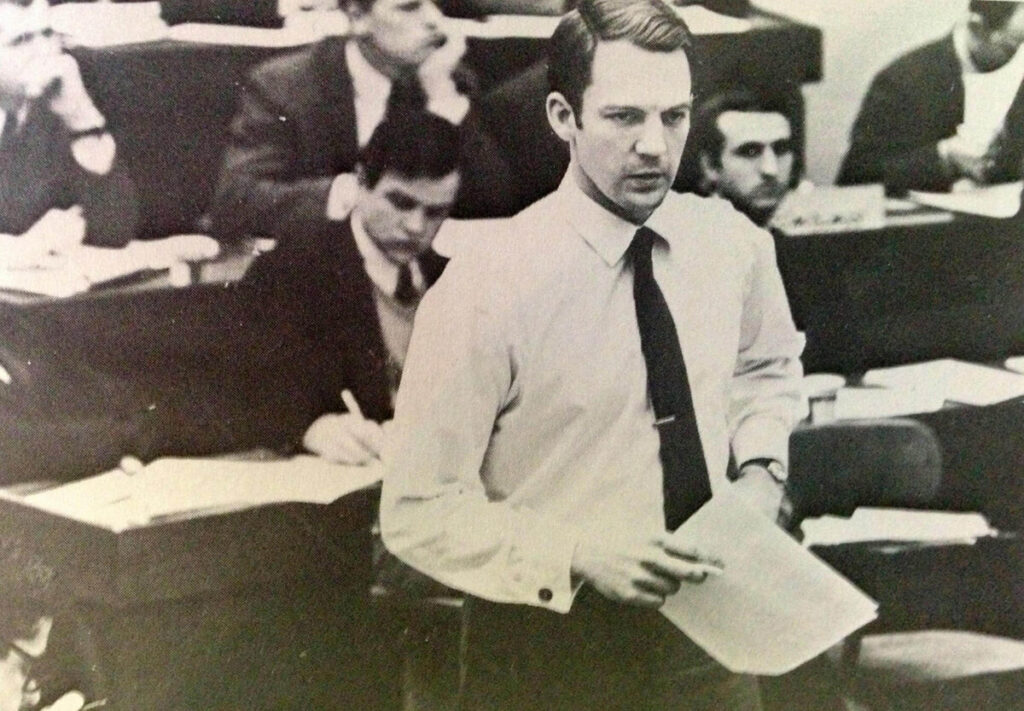

My father passed away peacefully on December 30th, 2021. The photo is from a time before I knew him, taken when he was 27 years old as a professor at the Harvard Business School. I chose it because he thought that one of the best things you can do in life is to help people learn and grow. It was an unwavering constant. As a student at HBS, his thesis, titled Financial Performance of Conglomerates, was published and it won the Richard D. Irwin Prize for the Best Doctoral Dissertation (1968-1969). I recall him telling me how difficult it was to write, and that he was tempted to abandon the effort. He exhausted himself researching the subject, and his frustration mounted as he ran out of people to call on.

He only shared this story with me once, and to understand why requires knowing him. My father never felt the need to be the loudest person in the room. His mind was magnificent and multi-faceted, but he navigated his professional career and personal life with little ego, which made him all the more remarkable. The purpose was not to communicate that his book was awesome or that he was brilliant. The point was to highlight the realization that caused his frustration to dissipate; he had run out of people to call because exhaustive work had made him the authority on the subject. In other words, he had become the person to call.

In response I told him I would read it immediately, but he told me not to. I was employed at the private equity firm he founded at the time, and he said he could teach me more without it. The technical knowledge in the book was not what he wanted to share. It was the idea that I could become an expert, in any field, by choosing to.

I was fortunate to spend 8 years working with him in the same office. The learning curve was steep. His partner, John Benefield, a man I came to admire immensely, gave me enough work to pull two all nighters my first week on the job. The training I had received previously was not enough, and I worked constantly to live up to their standards. After about a year on the job, my father came into my office requesting analysis that he wanted to review the next morning. I let him know I could complete it in 15 minutes if he was willing to wait. He gave me a skeptical stare and asked me to show him as he looked over my shoulder. When I completed the task, an enormous grin appeared on his face. “I didn’t know you could do that,” he said, his face beaming. I lived for those moments.

On many evenings, when the office emptied, I would sit in his office at a large oval conference room table (the same table I use to record most ASM videos today). Topics of conversation included business strategy, fairness, values, and personal relationships, to name a few. Most of what I know about how this world operates I learned working with him. It will forever be the highlight of my professional career, and it gave me confidence that I never had before.

In one of our meandering conversations, he asked me if I would ever consider teaching. Unbeknownst to him, I had written a manual describing how to build a three-statement model at my prior job as an M&A analyst. When I mentioned it, he encouraged me to share it with others. A few weeks later I drove to Best Buy and purchased a microphone for $25.32, and that evening I recorded the first video for what would later become ASimpleModel.com.

I chose the name because I was always fascinated by his capacity to make complex topics simple to grasp. Great teachers realize the tradeoff between the effort required to explain a concept and the effort required to understand it, and they devote themselves to the former. Long pauses were a signature of his speech, and he used them to craft explanations that could be absorbed with little effort. He is the reason I enjoy sharing knowledge, and I can only hope to live up to his legacy.