Over your investing life, you may have had the opportunity to participate in various types of funds (PE, VC, public markets, credit, real estate, etc.). Or maybe you would simply like to have that opportunity in the future. Regardless, you should know the best practices that experienced LPs follow as they decide whether or not to place money in a particular fund. Not all LPs are the same, of course, in terms of risk tolerance, preferred investment style, or diversification needs, but there are widely applicable rules that can maximize your expected return from a fund while minimizing the chance of losing your shirt.

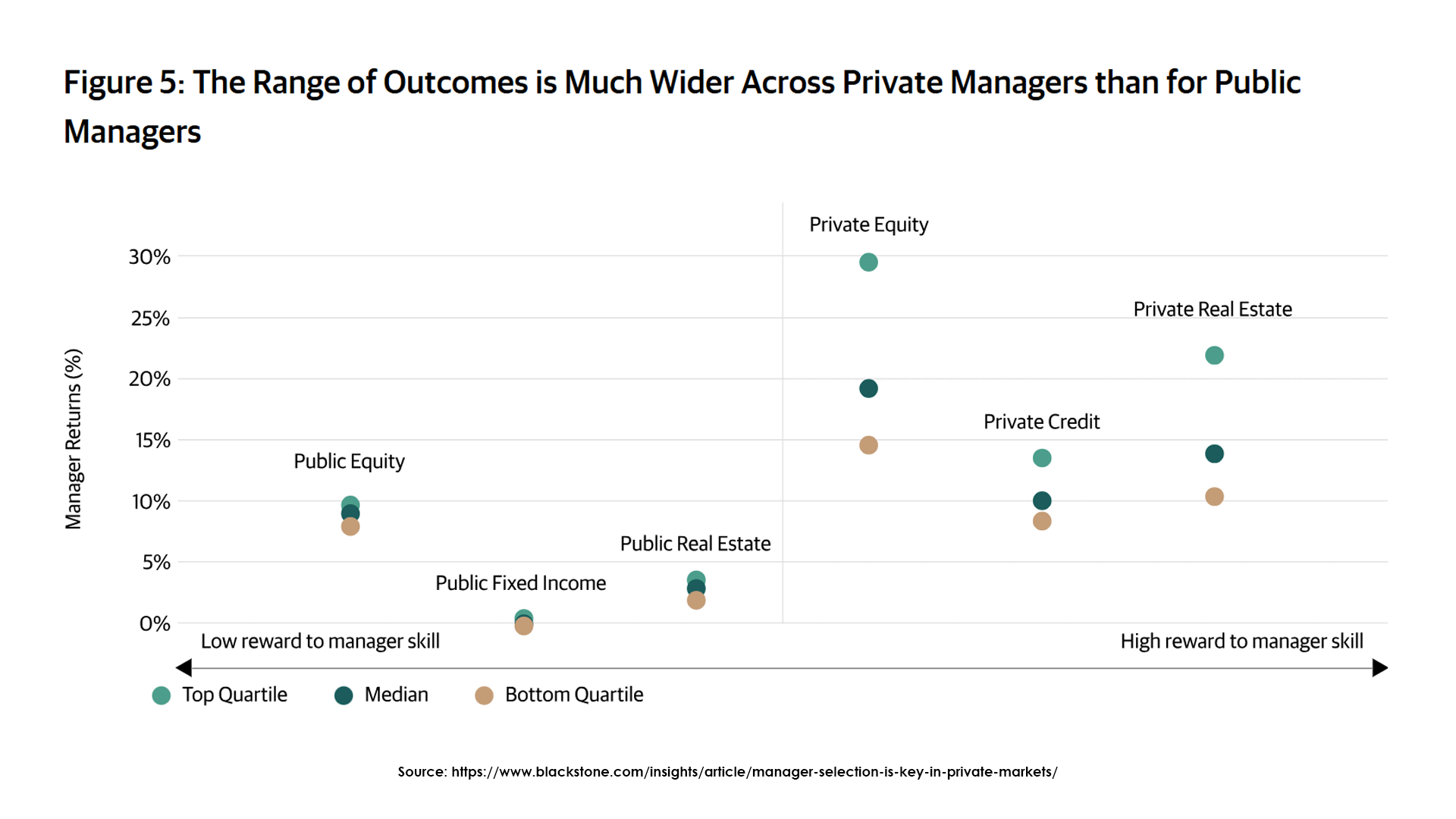

Many of these principles are relevant across different types of funds. But I will especially focus on private equity, because that is arguably where manager selection matters the most, due to long lockup periods and return horizons, not to mention the lack of an easy barometer for by-the-minute performance. As the figure below shows, managers in private markets have significantly greater variance in outcomes (along with better overall returns) than do public market managers.

Figure 1. In Private Equity, Managers Matter More (source: https://www.blackstone.com/insights/article/manager-selection-is-key-in-private-markets/)

Furthermore, an ongoing deceleration in private equity markets now has us in what McKinsey calls “a slower era” generally, with private market fundraising falling 22% globally in 2023. Not all areas of private equity are experiencing these difficulties equally, but it still underlines the fact that selecting the best private fund for your money is more important than ever. You can no longer expect a rising tide to lift all boats.

Before getting into specifics, I want to lead with two general observations. The first concerns a critically important aspect of any worthwhile PE fund—its investment mandate. This is not just a strategic statement, but a binding legal agreement between the fund’s managers (GPs) and investors (LPs) specifying the types of positions the fund’s money can be placed in. The mandate narrows the universe of investable assets by identifying geographies, customer segments (B2C, B2B, etc.), business sizes (middle market, etc.), or other characteristics where the fund will focus its efforts (and also when that focus can be deviated from). Experienced LPs would never put money into a fund lacking a clear mandate. You shouldn’t either, even in the face of a charismatic manager or pitch that may sound otherwise appealing.

The second piece of advice is frequently heard but too often unheeded. One of the most important character traits any investor should cultivate is skepticism. Assuming your net worth is south of eight figures, there may be some negative selection bias at work in the funds that are open to you, and especially in those that approach you proactively. The key to finding the best fund for your money is doing superior diligence that gets below high-level, cherry-picked numbers such as IRR (which can be gamed in multiple ways) to illuminate the full picture. Think of yourself as a reporter digging for the truth, while also following a diplomat’s “trust-but-verify” approach. Always try to validate information from a manager with information from other sources (other investors, former employees and associates, public databases, etc.). Professional LPs do significant outside diligence and reference checks to ensure that any managers they speak with are not feeding them a “rainbow and unicorns” story.

With that general advice in mind, in the bullets below, I break down how to analyze a fund and its team both quantitatively and qualitatively. And if you want a deeper dive into topics such as the various methods for doing public market equivalent (PME) analysis—which can identify how much of a manager’s performance is attributable to generally rising public markets—I recommend this article from eVestment’s Cameron Nicol.

How to Analyze a Private Equity Fund

Track Record & Through-Cycle Performance: Fund diligence at its most basic is about assessing whether a manager or team has the skills to generate outsized returns over the next 5-10 years, and the best way to do this is typically looking at a fund’s (or manager’s) prior track record. You should always be confident you wouldn’t be better off investing in something less opaque and risky, like the S&P 500, particularly when taking into account the higher fees and reduced liquidity common to most PE funds. For managers with little or no history to draw from (which is increasingly the case as private equity welcomes more women and minority GPs), they still need to demonstrate their potential in other ways. This could be through stellar experience at a prior firm, deeply embedded industry connections, or a well-articulated, unique vision that holds up to close scrutiny (ideally, all of the above).

With the economic environment slowing, it is also increasingly important, when possible, to investigate a manager’s past performance through a full business cycle. As Jess Larsen of Briarcliffe Credit Partners notes about the current PE market, “the manager’s track record during the [2007-2008 financial crisis] and their workout capabilities will be high on the LP’s due diligence agenda.” Always compare this performance to a benchmark of similar investments (sector, size, geography, etc.), and trace the sources of outperformance (How PE Firms Generate Returns | ASM) to understand how the strategy that led to past success might perform in a weakening business climate.

Terms: Look closely at terms such as management and performance fees, lockups, and hurdle rates that the fund is offering to investors, and whether they are negotiable. Compare these to other similar funds, either through independent research or by speaking with other investors in your network. Are there opportunities for “co-investment,” in which LPs can invest money directly into specific opportunities alongside the fund with reduced fees on a deal-by-deal basis? Co-investment is increasingly important to LP economics, and according to Pitchbook grew from $4 billion in 2010 to $10.3 billion in 2022.

Structure, Governance & Reporting: LPs increasingly crave transparency to see what is happening “behind the scenes” at a fund, as well as governance that is accessible, candid, and responsive (something particularly important if the portfolio starts to sour). Strong advisory boards that can provide independent oversight on valuation and conflicts of interest are a plus, as is a fund that reports as much information and provides as much access to its dealmakers as possible. In this tech-enabled investing environment, LPs are increasingly data-hungry. They want performance and tax data that is not only detailed, but timely, accurate, and as clear as water. Generally, any major deviations from industry standards in terms of a fund’s structure, governance, or reporting practices should be investigated, and should have a clear and compelling reason behind them.

Specialization: We have written before about why many PE funds are “niching down,” to specialize along sector, geographic, methodological, or other lines (Specialization and Private Equity | ASM). First and foremost, as large LPs always do, you should make sure that the niche the fund occupies makes sense within your broader portfolio exposure. Additionally, as an investor evaluating a specialized fund, you need to think deeply about how unique the niche is, whether you have sufficient understanding of it, and whether the team has the knowledge and networks needed to generate excess returns within its confines. Specialization should always align with the demonstrated background of the team. A fund specializing in operations improvement, for instance, should be loaded with individuals that embody that type of expertise (former executives, lean operations and supply chain experts, etc.), which leads us to our next bullet.

Team & Capabilities: Though some may not find it as comfortable as evaluating a manager’s quantitative record, a thorough due diligence includes getting to know the team members as individuals and as a group. Do incentive structures sufficiently align their interests with the investors? Are their backgrounds complementary to each other? Experience working together is a definite plus. And since conflict in private equity work—either constructive or destructive—is a given, learn or intuit as much as you can about the team’s interpersonal dynamics. Most large LPs will also run in-depth background and reference checks on at least the senior members of any new fund they’re investigating.

Sourcing & Investment Process: Any good fund should be able to articulate a demonstrable advantage in expertise or approach that will both ensure they’re near the front of the line for deals they want, and able to quickly weed out ones they don’t (this is particularly important in growth/VC-focused funds). Strong track records, broad industry networks, and proprietary deal identification/cold calling procedures can all be major assets in deal sourcing. On the investment process front, spend as much time as you can analyzing the team’s due diligence approach to determine if they have a clear process that can be relied on to uncover, negotiate, and close deals that have superior return potential, in both down and up markets. Remember that once your money is invested, you will typically not have any input on these matters, so if a fund is just doing what everyone else is doing, it’s probably not worth handing them your money and waiting 5-10 years to see how it turns out.

The End Result: A Process of Your Own

If you conscientiously apply all the points above to your own investment search, over time you will distill from them a philosophy and process of your own, something repeatable that you can stick to and that becomes quicker and easier to implement the more you do it. This is critical to superior investing, because research demonstrates that all types of investors—even career LPs—can be prone to biases (https://www.evidenceinvestor.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/SSRN-id3910494.pdf). Discipline is how you circumvent that.

Together, your quantitative and qualitative analysis should work together like an autostereogram—those pictures in which a hidden, three dimensional image emerges when you gaze at them correctly. That picture, if you can bring it into focus through disciplined diligence, will help you separate the best of investment funds from the rest of them. The next post will continue this line of inquiry by explaining what LPs look for when they get an opportunity to invest directly in a deal rather than in a managed fund.