In the world of private investing, agreements between businesses and their creditors can be as daunting to read as Tolstoy’s War and Peace. But among the many aspects of a loan that these documents spell out (duration, maturity, interest rate, securitization, seniority, etc.), one of the most crucial to understand is covenants.

The word comes from the Latin convenire, meaning “to come together” or “to agree,” a pretty apt description of a loan covenant’s purpose. Or put differently, covenants can be viewed as “relationship guidelines” set by borrowers and lenders, which not only outline expectations from both sides but also specify penalties for violations. Such breaches can escalate to a loan default — or to extend the relationship metaphor, a breakup.

For lenders, covenants are risk reduction tools that force the borrower to act in responsible ways and hopefully ensure the loan is paid back on time and in full (or alert the lender when that becomes less likely). For borrowers, agreeing to covenants is a way to not only access necessary credit, but also receive the most advantageous terms (i.e., lowest interest rate) possible. That said, one really interesting thing about covenants is how they have evolved since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008.

Pre-GFC, private leveraged loans were heavy on “maintenance” covenants. These require borrowers to maintain certain financial ratios and metrics (e.g., debt-to-EBITDA or fixed-charge-coverage ratios, which we’ll discuss more later) on a constant and ongoing basis. If the specified numbers get out of bounds, lenders may be entitled to declare the borrower in default and take control of the business, as many did during the GFC. It is important to note, though, that in most cases, lenders are not equity investors and do not want to be running businesses – they want to be issuing or buying debt at fixed returns; thus, even during the GFC, many lenders waived covenant violations to allow businesses to avoid default.

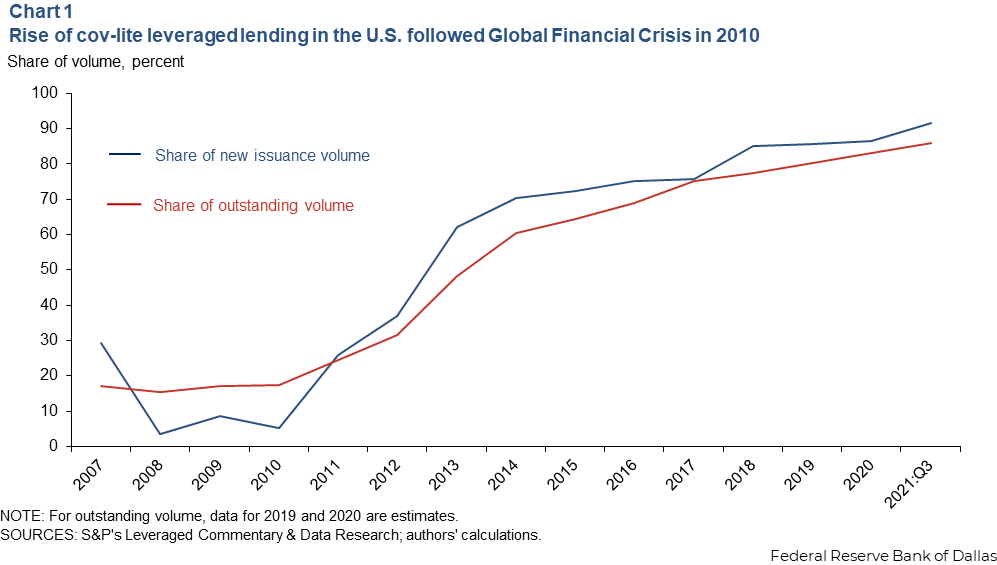

Post-GFC, covenants began to change. With public investments facing stiffer regulations, and with monetary authorities holding interest rates near 0% for years, credit investors seeking better returns started flooding the private, high-yield market with capital (Private Credit Overview). According to a report from the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, the high-yield market more than doubled in size between 2008 and 2019, reaching $1.2 trillion in outstanding debt. With so much money flowing in, high-yield credit became very much a borrowers’ market. And with creditors desperate to deploy their dry powder, they competed for deals by offering friendlier credit agreements containing fewer maintenance covenants. The graph below shows the remarkable growth of these “cov-lite” loans, which increased from less than 20% of the market in 2007 to 86% in 2021.

Despite being light on maintenance covenants, these deals typically still contain “incurrence” covenants, which govern specific actions a borrower might take, such as making a new acquisition or taking on additional debt, by either prohibiting such actions outright or specifying the conditions under which they are allowed.

Some commentators think this explosion in cov-lite credit represents a dangerous lowering of lending standards along the lines of the subprime mortgage bubble that preceded the GFC (LINK). Others argue that incurrence covenants are actually a more efficient way to discourage risky behavior by borrowers, doing “more with less” while eliminating the need for constant metric monitoring (LINK).

Time should tell which view is right. In the meantime, covenants of all types continue to exist and appear in loan agreements. At times they can take on very specific and quirky forms, depending on the deal at hand. I once even heard a rumor of a covenant that specified the colors allowed for cars leased by the borrowing business, presumably to force the company to maintain a certain image!

Car colors aside, below are some of the most common loan covenants you are likely to encounter in private credit deals.

Common Private Credit Loan Covenants

There are a number of general categories that can be applied to loan covenants. The maintenance/incurrence divide that we discussed earlier is one of these. To briefly mention a few others, “standard” covenants are those found in a large proportion of credit agreements (such as a requirement for periodic financial reporting), while “non-standard” covenants are atypical stipulations tailored to the specific deal at hand (for instance, that the borrower must not lose a certain critical customer). “Positive” or “affirmative” covenants require an action on the part of the borrower (such as keeping certain insurance coverages), while “negative” covenants restrict actions (such as prohibiting the sale of specific assets). “Financial” covenants come in two subtypes—”cash flow” (income statement) or “balance sheet” covenants—depending on which financial statement they relate to. “Non-financial” covenants, on the other hand, relate to operational practices or standards (for instance, a requirement to keep certain key personnel employed by the company).

As you can see, loan covenants are talented shape shifters, capable of taking a myriad of forms to suit a specific credit situation. Some types of covenants, however, are especially common, such as those listed below.

Maintain Financial Ratios Within Specific Boundaries

Balance-Sheet Ratios: Below are two balance-sheet ratios very commonly mentioned in both maintenance (borrower must remain in regular compliance) and incurrence (only “tested” if the borrower is attempting to take some action such as an acquisition) covenants, though the precise way they are calculated may vary from loan to loan. The idea is to help prevent borrowers from substantially altering their balance sheet by overleveraging and putting repayment ability in jeopardy.

- Debt to Equity (D/E) – This ratio gets at a firm’s financial leverage by dividing its total debt by total shareholder equity. Though the normal range varies by industry, a higher D/E ratio generally signifies a business that is at greater risk should an unforeseen problem (e.g., a decline in sales or a recession) occur.

- Debt to Assets (D/A) – This gives another view of a firm’s leverage by dividing total debt by total assets. A high figure indicates a firm whose assets are heavily reliant on borrowing, which signals risk.

Cash-Flow Ratios: Below are two cash-flow ratios often referred to in various covenants. Establishing guardrails on these metrics helps ensure the borrower does not end up in a liquidity crunch that may prevent them from paying back interest or the loan principal.

- Debt to EBITDA – Dividing total debt by EBITDA is a fundamental measure of a firm’s repayment ability. While it varies by industry and situation, values above 4-5x can be a warning sign to many lenders, particularly further into the duration of a loan.

- Fixed-Charge Coverage Ratio – Another key measure of repayment ability, this ratio is typically calculated as cash flow (adding back dividends and unfinanced capex) divided by fixed charges (primarily interest/principal payments, leases and other fixed obligations). It illustrates how easily a business can cover its regular, unavoidable (fixed) expenses—such as rent and debt payments—with its earnings.The higher the ratio, the less risk there is from a creditor’s point of view, with anything below 1.0-1.25x being seen as a warning sign.

Refrain from New Debt Issuance or Moving/Selling Collateral: When a loan is made, lenders specify certain collateral, seniority, maturities, and interest rates based on the borrowers’ existing capital stack and business conditions. For this reason, they often want to restrict the borrower’s ability to take on new debt that may supercede them in the stack or simply create additional claims on the company’s assets. They may further feel the need to restrict the selling or shifting of collateral to subsidiaries over which the lender has no clear claim. This has become a much bigger concern in recent years, as borrowers have been finding ways to exploit more generous credit agreements and shift around collateral to access new debt at the expense of existing creditors. In one famous instance of this, fashion retailer J. Crew cleverly shifted pledged assets (primarily its brand IP) to a subsidiary in order to acquire new loans against them, leaving the existing creditors who had lost their privileged claim “J. Screwed.”

Limit M&A or New Dividend Payments: Lenders tend to worry about activities that significantly alter a borrower’s cash profile. There are a variety of covenants they may put into place to limit operational activities that carry this risk. One of the most common is restricting mergers and acquisitions (often above a certain size) without lender approval. Similarly, they may restrict payments of dividends to equity holders except under certain conditions (such as if the payment in question is below a pre-set threshold relative to earnings) in order to limit money exiting the business.

Provide Periodic Financials and Reporting to Lenders: Though they may be less onerous in these covenant-light times, credit agreements still commonly specify quarterly and annual reports (covering both key financial and operational metrics) as well as audits that must be made available to lenders in a specific form so that they can monitor the borrower’s ongoing financial health.

Other common covenants may require the maintenance of a certain credit rating, compliance with relevant industry regulations, adequate insurance coverage, minimum levels of cash or inventory, and lender approval of leadership or ownership changes. In the case of financial covenants, it is also worth noting that the exact threshold required for something like a debt to EBITDA ratio may evolve across the duration of the loan, based on a schedule in the credit agreement.

The penalties for violation of covenants (or at least a violation that is not “cured” within a stated remediation period) can vary from fines, to changes in loan terms (such as a higher interest rate, accelerated repayment schedule, or increase in required collateral), to an all-out default that could trigger a collateral seizure or even a transfer of operational control to the lenders.

Conclusion: Know Thy Covenants and Communicate Well with Thy Lenders

At the end of the day, covenants give creditors some level of control over how borrowers run the underlying business, which allows them to be more confident lending at appealing rates and terms. Thus far, the impact of burgeoning cov-lite credit agreements since the GFC has not been tested by a sustained downturn (other than the brief blip of the COVID-19 pandemic). But with an ongoing search for returns in the fast-growing private credit space, it will continue to be a topic of speculation and legitimate concern.

In the meantime, you should approach any credit agreement’s covenants, light or not, carefully, understanding every nuance before either investing or borrowing. Borrowers, particularly in a prolonged period of economic growth such as the 2010s, have a tendency to view covenants somewhat flippantly or as a meaningless formality to appease lenders. But as an informed borrower, it is vitally important to run through every worst- or even “slightly-worse-” case scenario to make sure you are unlikely to trip covenants throughout the life of a loan, even if you think the probability is relatively slim. Because though written on paper and in pixels, once signed they are practically set in stone.

That said, under the right circumstances and with a cooperative debtor-creditor relationship, lenders may be willing to excuse temporary covenant violations, as we discussed briefly above with respect to the GFC. During the pandemic, the airline industry, which saw a sudden and historic collapse in demand, managed to obtain covenant “holidays” and extended cure periods to help maintain solvency until the financial storm passed. As with so many things—including the dynamic between private equity management teams, boards, and investors—open and honest communication between borrowers and lenders can make all the difference in avoiding a default when the unexpected happens. On the other hand, if communication turns sour, it becomes increasingly likely that lenders will pursue every recourse available to them, which is why careful drafting and understanding of all covenants in a credit agreement is so crucial for borrowers.