At ASM, private credit is like a long-lost cousin to our typical topic of discussion, private equity, that we haven’t talked much about. But that needs to change, because private credit has experienced tremendous growth as an investable asset, with a particular boom in the last two to three years. The reasons for this are multi-faceted, but include the fact that increasingly stringent regulatory environments are driving money away from traditional banking into less regulated and more flexible private markets. And as new banking regulations such as Basel III Endgame take effect, we expect this trend to continue, with private credit becoming more accessible to a broader swath of borrowers and investors.

With that in mind, this primer—the first of three posts exploring private credit—will provide you with more insight into this interesting and potentially lucrative class of assets by placing it in the context of the broader landscape of debt financing and helping you to understand some of the key features of different credit instruments.

Overview of Different Types of Credit Instruments

Private or Public: Just as equity investing has its public and private side, so does credit investing. Traditional corporate or government bonds comprise the public side of the market for debt. These are registered securities regulated by entities such as the Securities and Exchange Commission in the United States, and typically have a fairly deep and liquid secondary market beneath them, which investors can use to exit when they are ready. Private credit instruments such as leveraged loans may also have secondary markets, but trading is more often limited to sophisticated institutional investors. Private debt is more likely than public debt to have the originator still holding the loan, to have floating rather than fixed interest rates, and to cater to smaller and middle-market businesses with a comparatively higher risk of default.

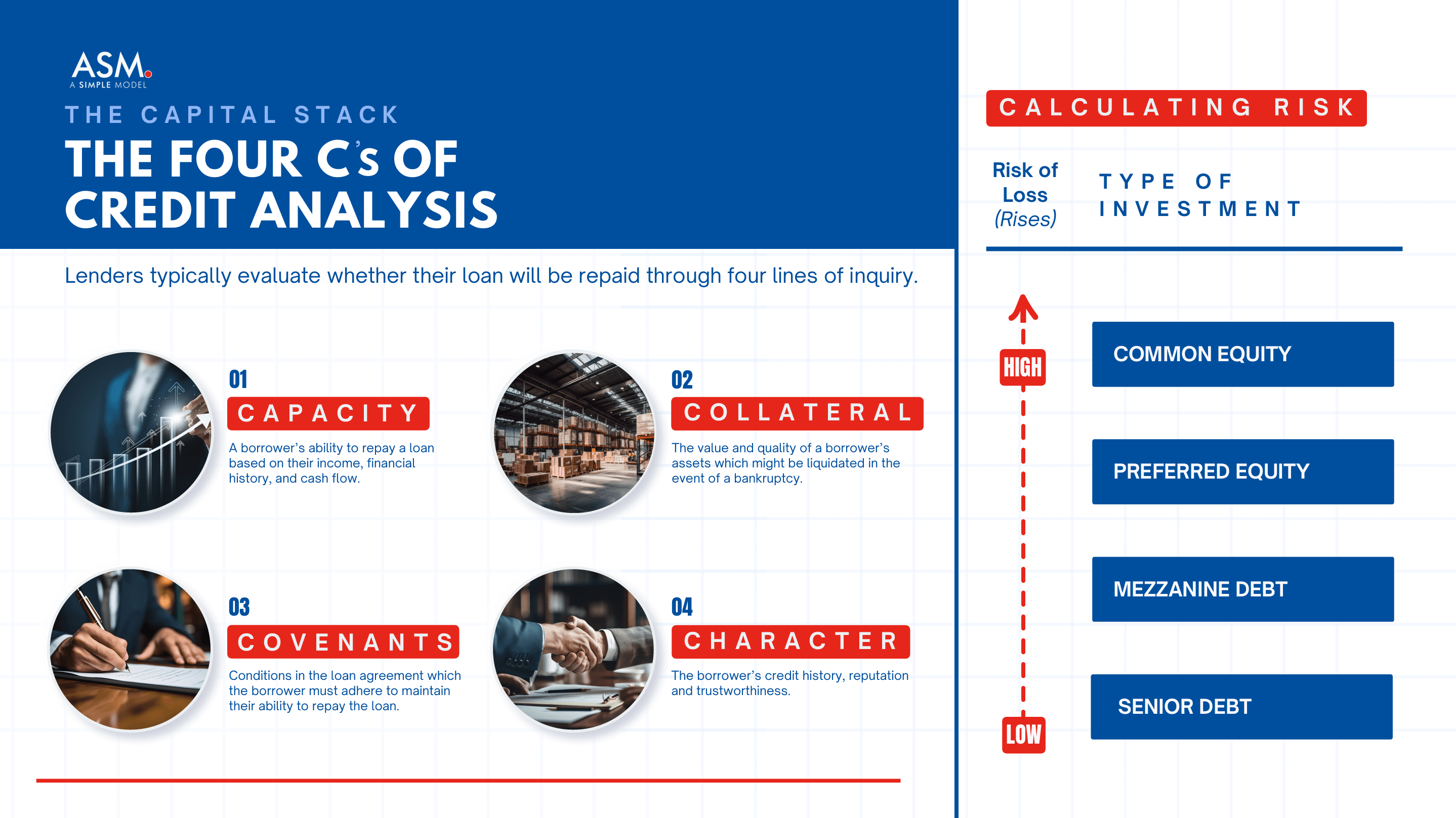

High or Low Position in the Capital Stack: Debt exhibits a greater diversity of forms than does equity, and perhaps the most important differentiator is the relative position in the capital stack (see image below). Think of it as the queue for getting your money back if things go bad. When a debtor goes bankrupt and has to liquidate, private debt holders with more senior positions get paid first, and those with a secured claim on particular underlying collateral such as real estate, equipment, or even an intangible asset such as brand, can be in an especially strong position relative to other creditors.

Fixed or Floating Rates: Fixed interest rates, which are typical in bonds but atypical in private loans, pay a set coupon rate (e.g., 7% or 700 basis points) over the life of the loan, which exposes the creditor to interest rate risk as market rates fluctuate. Floating rate instruments, on the other hand, change or “float” with a predetermined benchmark or “reference” rate, insulating the borrower from market rate movements (good or bad). In a loan agreement, a floating rate is expressed as the reference rate (e.g., SOFR) plus an additional amount (e.g., 6.25% or 625 basis points). Common benchmark rates include the fed funds rate, the prime rate, and SOFR (Secured Overnight Funding Rate), the latest values of which are easy to look up online. The latter rate, SOFR, has now replaced the previously-common benchmark LIBOR (London Interbank Offered Rate), which regulators had determined was prone to manipulation. (https://www.aier.org/article/libor-is-out-sofr-is-in-what-it-means/)

Primary Issuers or Secondary Buyers: Primary issuers are the original creditors who make a loan and agree to its terms (rate, collateral, covenants, etc.) with the borrower. Sometimes, especially in the case of private credit instruments, these lenders (occasionally referred to in the private space as a “club”) simply hold the debt to maturity. But in some cases they may sell some or all of it to investors in secondary markets, at a price that reflects the latest view of the borrower’s credit worthiness, as well as broader market and economic conditions. The price is often expressed as a percentage of the instrument’s face or “par” value, with prices above 100 indicating a premium and prices below 100 a discount. An instrument with a face value of $1,000 that is selling at 95, for instance, will cost you $950. Credit securities selling at a heavy discount, such as 60 or below, will typically be considered “distressed” assets, and investors should approach them carefully. A different indicator of quality is an instrument’s credit rating from Standard and Poor’s, Moody’s, or Fitch. A rating of BBB or lower is considered to be non-investment grade or “junk” credit (an arguably misleading term). Private credit instruments usually fall into this non-investment grade class, though they could still be a promising investment and possibly even selling at a premium.

Conclusion: The Private Credit Space Has a lot to Offer Borrowers, Lenders, and Investors

Borrowers like the private credit space due to its less regulated nature and the ability to customize terms. For lenders and investors, private credit represents a unique and increasingly popular asset class within a non-bank, non-publicly-traded environment. It offers better yields than traditional fixed income, but with added risk and reduced liquidity. In this sense, it shares quite a bit in common with our usual subject around here, private equity (and in fact is often carried out by many of the same firms). That said, there are also a number of important differences between the asset classes, which we will explore in the next post.