What good is a plan developed by the wrong team, or without the right team to execute on it? Follow the logic of those two questions and one thing becomes clear: before you do anything else, make sure you put the best talent in the best places. In other words, get the WHO right, and the WHAT will follow.

Author and management expert Jim Collins understands this about as well as anyone I’ve read. His book, Good to Great, explores “Why some companies make the leap (to greatness)…and others don’t.” What I love about this book is the research that supports its findings. Collins did serious work, putting together a 21-person research team and spending five years leading a project to divine what allowed a subset of decent companies to not only become great companies, but sustain that outperformance for at least 15 years. His team evaluated over 1,400 businesses and read and coded some 6,000 articles and 2,000 pages of interview transcripts.

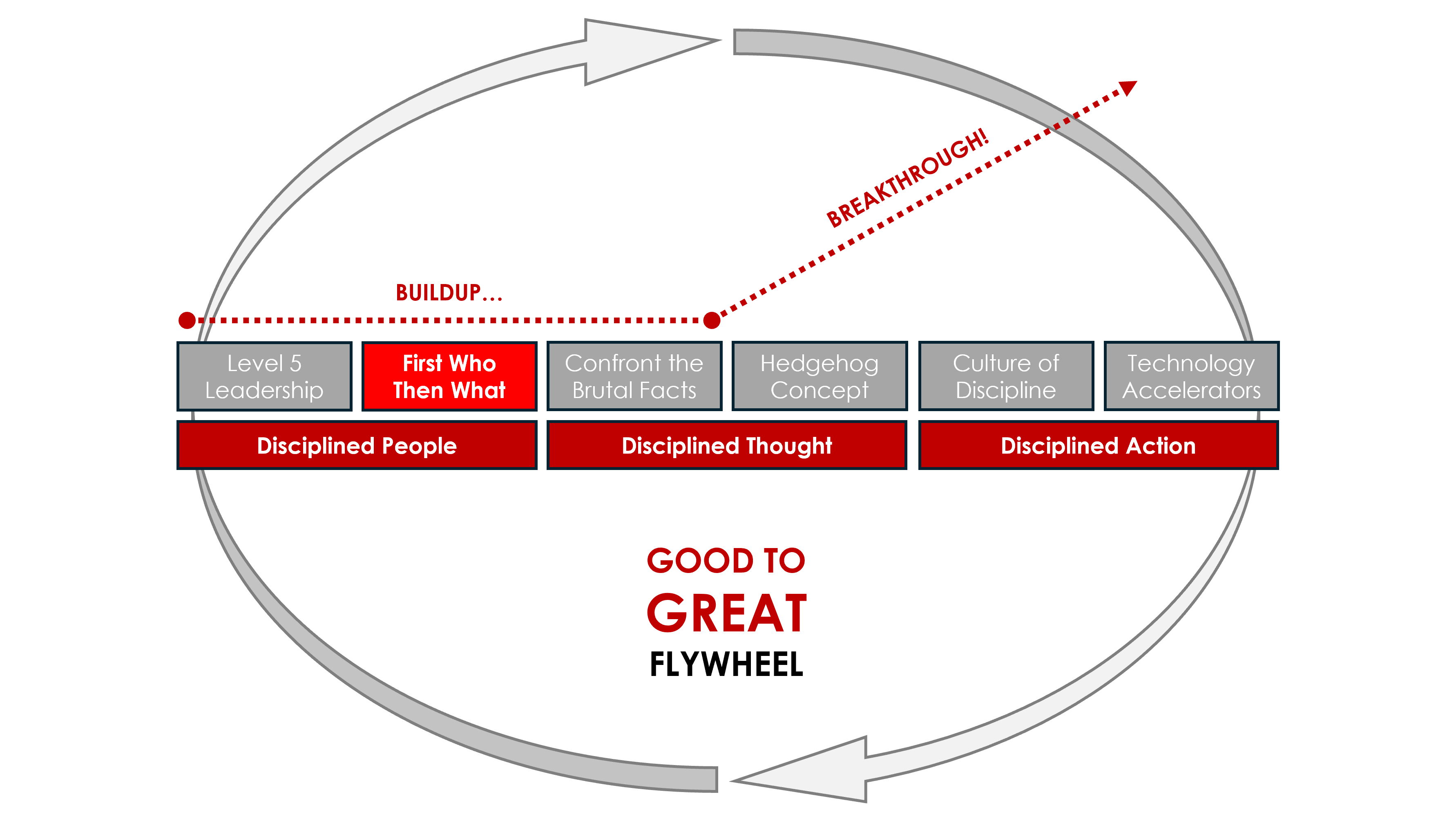

For companies trying to escape mediocrity, the consistent theme for those that succeeded was a keen focus on getting the “right people on the bus,” meaning identifying and recruiting not only exceptional people, but the correct skills for the correct positions. In the book’s “Good to Great Flywheel” (see illustration below), disciplined people come before disciplined thought and action. And it all starts with what Collins calls “Level 5” leaders with an incurable need to see results. The hallmark of a Level 5 leader is humility with a fierce resolve. These two traits are not typically found together, which is what makes these people so exceptional and able to drive extraordinary outcomes.

Alan Wurtzel, for instance, whose tenure as CEO of pioneering big box electronics store Circuit City lasted from 1972 to 1986, saw his company’s stock beat the overall market 18.5 to 1. It’s no coincidence that, from day one, Wurtzel had a legendary focus on getting the best employees. While competitors had banners on their stores promoting the latest sales, those at Circuit City said, “Always looking for great people.” This people-centric philosophy spread from Wurtzel down through the org chart. One vice president during Wurtzel’s tenure, when asked to name the top five factors that lead the transition from mediocrity to excellence, wrote “people” in every spot.

In another example from the book, after assuming the role of CEO at Gillette in 1975, Colman Mockler, Jr. spent 55% of his time the first two years making changes in the management team. In total he moved or changed 38 of the top 50 people and was quoted as saying that “Every minute devoted to putting the proper person in the proper slot is worth weeks of time later.”

On the flip side of this statement, the authors of Who, a New York Times bestseller that explores how to make good hiring decisions, claims that the average hiring mistake costs 15 times an employee’s base salary in hard costs and productivity losses. Imagine a $100,000 hire costing a company $1.5 million! It’s no wonder The Economist once referred to bad hiring as the “single biggest problem in business today.”

Another firm that made the cut into Collins’ book was steel company Nucor, which let the quality of potential employees drive its choice of new locations. Instead of traditional steel centers like Pittsburgh, it built mills in places like Crawfordsville, Indiana, specifically because it wanted access to farm communities and the people in them which Nucor had determined possessed exceptionally strong (and very hard to teach) work ethics.

According to Collins, it all comes down to Packard’s Law from Hewlett Packard co-founder David Packer: “No company can grow revenues consistently faster than its ability to get enough of the right people to implement that growth and still become a great company.”

In other words, revenue growth and getting the right people are two variables which are not only highly correlated, but causality runs from the latter to the former. Packard’s people bias was on full display when he founded his company with Bill Hewlett. They flipped a coin to see whose name would go first. Packard won and placed Hewlett’s name in front.

In my experience, humans like that are exceptional to work with and tend to drive exceptional results in business settings. But that raises a legitimate objection: getting great people is far easier said than done. But the lesson to take is that you should make finding the right people your number one priority on almost any business project. Invest the resources necessary—financial, time, and otherwise—on the activity, trusting that it will pay the investment back with dividends. And if you can’t find the right person at a particular time, don’t be afraid to be patient until that person comes along.