We talk a lot around here about equity, debt, and their roles and potential pitfalls in the context of leveraged buyouts and other acquisition deals. But what about their roles in the ordinary course of running a company that you already own? How do managers, and in some cases investors, decide when to use equity versus debt to finance the cash needs of a business? At the end of the day, both are valuable and vital tools for running and growing a business, but the pros and cons of each need to be well understood. Using them interchangeably or haphazardly can be financially disastrous.

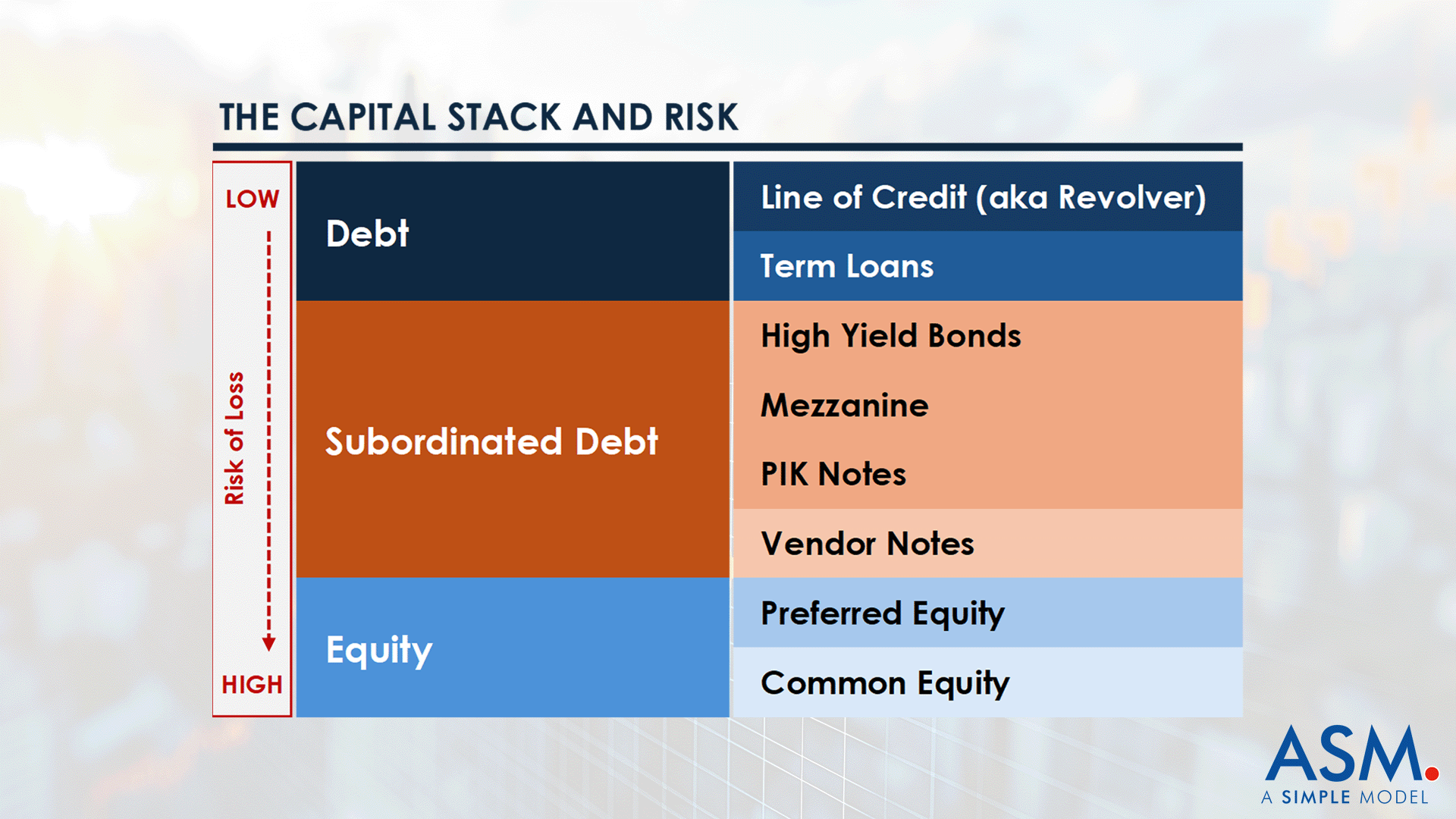

Many of the differences in these two financing methods are related to something we have talked about before—the capital stack (private credit primer). For our purposes, a capital stack is simply a breakdown of all the different funding sources that enable a business to operate. Equity and debt are both common and important sources of funds for a business, but as the capital stack below illustrates, when something goes wrong and a firm has to be liquidated, creditors always have priority over equity holders in getting their money back, which makes being an owner inherently riskier than being a creditor. This is a key distinction we will be returning to throughout our discussion.

Figure 1. The Capital Stack and Risk

The Basics of Equity Financing

Put simply, equity is a legal ownership claim on an organization’s assets and earnings. From the point of view of a business, issuing equity—whether by bringing in new owners or letting existing owners expand their stake—is an important option for raising needed cash, one that has its pros and cons, as we cover below.

Advantages of Issuing Equity

- It involves no obligation to repay principal at any specific time.

- It involves no regular, ongoing outflow of cash (i.e., for paying interest).

- It does not typically carry restrictions on how the money raised can be

- used or what the business can do going forward.

- It can bring in partners with new skills, contacts, or knowledge for helping the business succeed.

Disadvantages of Issuing Equity

- It can dilute the share of profits for the existing owners, which if the business is successful over time may outweigh the value of the immediate cash infusion, even on a time-value-of-money basis.

- It dilutes the existing owners’ control, potentially for the life of the business.

- It raises the possibility of new owners one day pushing the existing owners out of the business if they have sufficient control.

- It is typically a more “expensive” way to raise money than debt (though not necessarily on an ongoing cash-flow basis), because equity investors need to be compensated for the risk of having a lower priority than creditors in the capital stack.

Common Uses of Equity

While equity is not generally as “bespoke” an instrument as debt, there are variations (common stock, preferred stock, option/warrant structures) which allow firms to tailor an issuance to both fit their particular needs and appeal to investors. Young or upstart businesses often rely on equity financing because they may lack both the demonstrated profitability to qualify for a loan and the cash flow to support repayments in the short- to medium-term. Equity financing is also a popular choice for firms financing longer-term projects with uncertain odds of success, such as expansions into new markets or “blitzscaling” (risky and aggressive attempts to grow rapidly).

As an example of a business that scaled its operations to a very significant size primarily through equity, look no further than technology icon Alphabet, Inc. (formerly Google). It mostly avoided debt financing in its formative years by relying on equity infusions from investors such as Sequoia Capital and Kleiner Perkins, while also reinvesting profits. Strong cash flow growth didn’t hurt, either. In 2004 the firm went public in a $1.67 billion IPO, and the rest is economic history.

The Basics of Debt Financing

Debt, as most children learn early, simply means you owe someone something. In finance, the topic becomes a little more complicated, with debt having the potential to take on multiple forms with varying legal and financial ramifications. As with equity, issuing debt (in other words, borrowing) is an important option for businesses that need to raise cash. Knowing when and how to exercise it (https://www.asimplemodel.com/insights/what-is-private-equity-the-right-amount-of-debt) can mean the difference between profitability and bankruptcy.

Advantages of Taking on Debt

- It doesn’t dilute the share of profits for the existing owners.

- It doesn’t involve giving up meaningful operational control of how the business is run.

- It involves very clear, predictable repayments based on the loan agreement.

- It generally brings a tax deduction for interest payments (interest, remember, is a pre-tax expense).

Disadvantages of Taking on Debt

- It may be hard to qualify for, at least at an affordable interest rate, depending on the firm’s financial situation and market conditions.

It involves taking on a new operating expense in the form of interest and principal payments (most debt needs to be paid off or refinanced within 3-5 years). - It may in some cases come with limitations on what the firm can do with the money and how it can operate going forward (e.g., the firm may not be able to sell specific assets pledged as collateral, take on additional debt, etc.).

- It may require personal guarantees from the owners, putting their personal assets at risk in the event of a bankruptcy.

Common Uses of Debt

From old-fashioned term loans, to asset-backed loans (ABL), to convertible loans, to government loans, to revolving lines of credit (LOC), debt can take a myriad of forms (the details of which are beyond the scope of this post). But understanding and leveraging the bespoke nature of debt to tailor an ideal financing solution for a firm’s needs can be a significant advantage over equity issuance. From an operating standpoint, debt is most beneficial in situations where existing ownership believes strongly in the promise of future profits and does not want to give up operational control, even if that means sacrificing current cash flow.

Instruments such as revolving LOCs or ABLs are typically used for “ordinary course of business” financing or to fund more limited projects that involve significant assets with clear return profiles, such as buying equipment for a factory or acquiring a smaller competitor. More mature companies with established profit streams enjoy the easiest access to credit markets and therefore can rely more heavily on debt as a financing source (though this does not always translate into higher debt-to-equity ratios, for a variety of reasons). Despite all of that, at the end of the day, the appeal of debt remains highly dependent on the rate of interest. This is true for equity financing as well, but not to the same extent, because interest rates only impact the return demanded by equity investors indirectly, through factors such as investor expectations and opportunity costs.

An example of an iconic firm that found success through a significant use of debt financing, especially in its early years, is Tesla. Some of this debt was in the form of convertible bonds (which offer creditors the option of becoming equity holders at a later date) that helped the company fund research and development and build its factories.

The Bottom Line: Weighted Average Cost of Capital

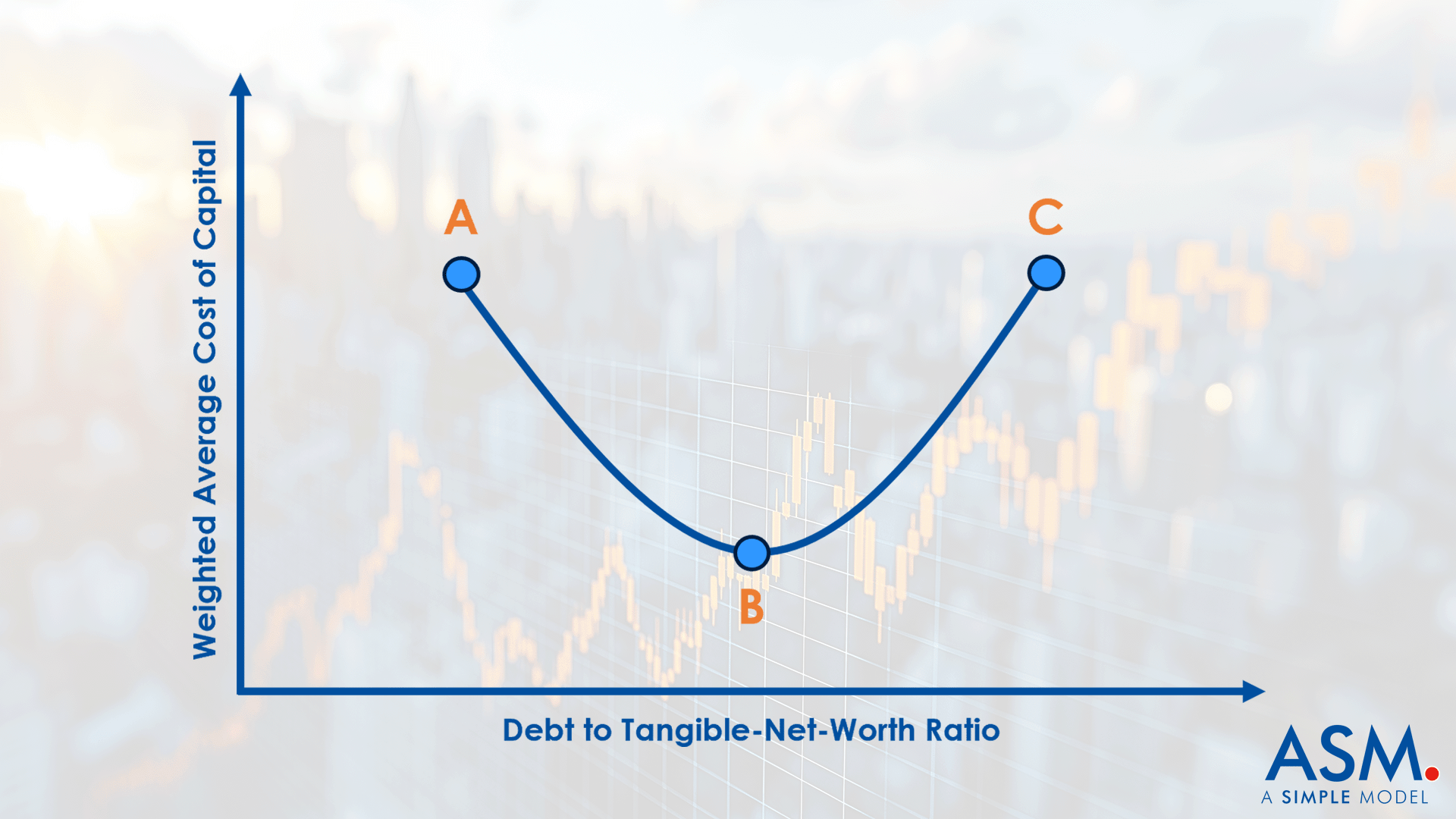

So, what is the best way for a business to raise cash, through debt or equity? Generally speaking, the correct answer is both. Though there are examples to the contrary, very few businesses of size today fund their operations through strictly debt or strictly equity financing. There is a principle at work in this fact, which the figure below Illustrates.

Figure 2. The Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC) Curve

The convex shape of the weighted average cost of capital (WACC) curve tells us that this firm’s WACC increases as the debt to tangible-net-worth ratio (D/T) becomes very low or very high (indicating the firm is using very little or a great deal of leverage). To understand why this is the case, think about point A. It represents a capital structure heavy on equity. That implies a high cost of capital because equity investors typically demand a higher return than creditors (due to being lower in the capital stack). From this point, increasing the proportion of debt in the capital structure will lower the WACC.

Now think about point C, which represents a capital structure heavy on debt. It will have a high cost because creditors will realize the business is becoming highly leveraged and demand a higher interest rate to compensate them for the risk. From this point, reducing the proportion of debt will lower the WACC.

The best place to be is somewhere in the middle, represented by point B, with a combination of debt and equity which minimizes the firm’s WACC. Like anything worthwhile, finding this financing “sweet spot” is never easy. It requires understanding the company’s financial statements, business model, operating plans, macro environment, and all the pros and cons of debt and equity we covered above.