Adjusted EBITDA is a very common metric that can be found in many investor presentations, which makes understanding EBITDA and acceptable adjustments to this figure important. Unfortunately EBITDA is frequently used as a proxy for cash flow. As the video featured in this post will demonstrate, it is anything but. In businesses that require heavy capital expenditures or those with heavy debt burdens, the discrepancy between EBITDA and cash is vast. Add to this the adjustments investment bankers and management teams will use to embellish or even exaggerate earnings and the metric can become meaningless.

EBITDA does have its purposes, however (as the Private Equity Training Curriculum frequently points out). In the context of debt service, EBITDA can be helpful because adding back interest expense, taxes and non-cash charges including depreciation and amortization, provides a quick back of the envelop approach to evaluating how much interest expense a company can tolerate.

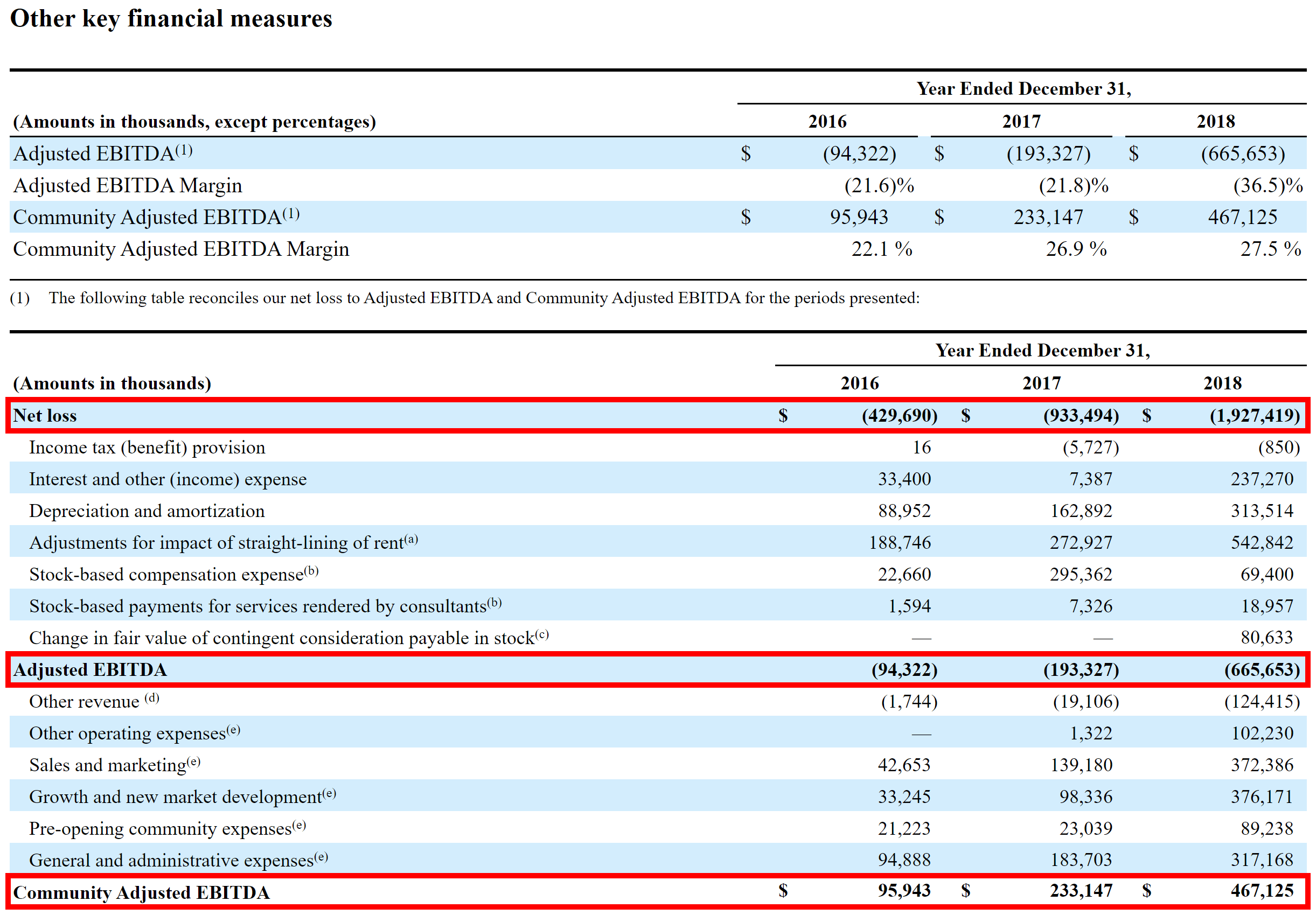

But, it has become pretty common for this metric to include additional adjustments when there’s an attempt to raise capital or sell shares to make the company look even more profitable than it is. WeWork arguably pushed the envelope on an otherwise common attempt to inflate earnings with words vs. dollars when it introduced an even more exaggerated version of adjusted EBITDA: Community Adjusted EBITDA.

It called the fully adjusted number “community adjusted Ebitda,” by which it subtracted not only interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization, but also basic expenses like marketing, general and administrative, and development and design costs. Those earnings were $233 million, WeWork said.

“I’ve never seen the phrase ‘community adjusted Ebitda’ in my life,” said Adam Cohen, founder of Covenant Review, a bond research company.1

In July of 2018, the FT punched back at WeWork’s valuation. CEO and cofounder Adam Neumann supported a lofty $20 billion valuation claiming that WeWork is a “community” and a “state of consciousness” that brings people together to “change the world.” In contrast, the FT reported:

WeWork’s claim to disrupter status in serviced offices also requires scrutiny. The existence of older providers such as IWG is the elephant in the office. Like them, WeWork has a business model underpinned by unglamorous property market arbitrage: leasing offices, fixing them up and renting them out at a higher rate. If the groups are fundamentally the same, it makes no sense to value WeWork at $20bn — more than 10 times expected sales.

IWG is the world’s largest serviced office provider, with more than 10 times the number of offices and a profitable business model. Yet it has an equity value below $4bn. This values IWG at 1.2 times forward sales. If valued at the same multiple, WeWork would be worth around $2.7bn.2

The word that should leap off the page is “profitable.” WeWork could not be compared to IWG based on profitability because it was on schedule to lose $1 billion annually at the time of this analysis. Well, at least based on any standard measure of profitability. Which brings us back to “community adjusted EBITDA,” which the FT skewered.

By stripping out almost every cost — from advertising to those associated with setting up new offices — this figure was positive at $233m last year. [CFO Artie Minson] says he received no pushback from investors. But such flattering bespoke measures of profits remain a red flag for many investors. Online coupon site Groupon abandoned its own individual measure after attracting negative attention. WeWork would be wise to do the same.2

For reasons that defy logic, SoftBank’s Masayoshi Son chose to ignore the red flags and pushed WeWork’s valuation to $47 billion in private dealings with Neumann by summer of that year. By October, just six weeks later, the valuation plummeted by 70%. Fast forward to May of 2020 and WeWork’s valuation stands at $2.9 billion.

1Eliot Brown | “A Look at WeWork’s Books: Revenue Is Doubling but Losses Are Mounting” | The Wall Street Journal | 4/25/2018

2Elaine Moore Eric Platt | “Lex in depth: Why WeWork does not deserve a $20bn price tag” | The Financial Times | 7/2/2018