Summary Text

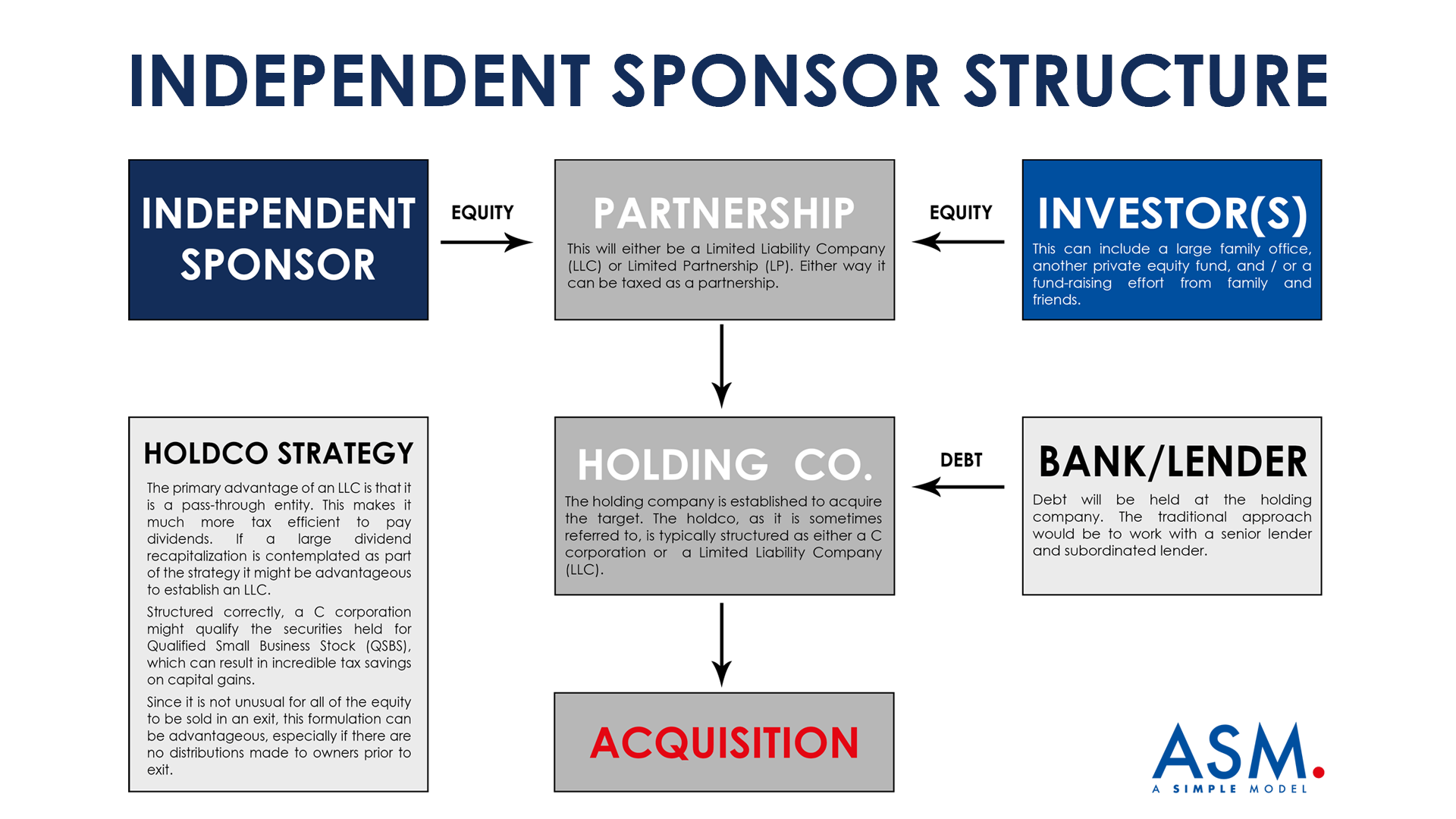

In contrast to a private equity fund, an independent sponsor sets out to source an acquisition target (business for sale), and then raises the funds to complete the acquisition. This can be achieved by an individual or a team of people working to raise capital on a deal-by-deal basis.

Whereas previously independent sponsors were considered limited to lower-middle-market transactions, private equity's rise in popularity as an asset class and the amount of capital available to deploy ("dry power") has made the independent sponsor approach increasingly popular. The task of raising capital has also been facilitated by a growing number of funds that target working with independent sponsors as part of their sourcing strategy.

As it relates to an introduction to the industry, the independent sponsor model is useful because it is focused on an individual transaction. This facilitates exploring how a transaction is closed before moving on to the funded approach. This lesson focuses on transaction structure, and the parties required to close a single transaction.

INDEPENDENT SPONSOR ECONOMICS:

On the subject of independent sponsor economics, the first thing to be aware of is that the economics tied to any particular transaction are subject to negotiation. As we will see in the lessons covering private equity funds, structures can vary from one firm to the next. This is perhaps even more exaggerated for independent sponsors where having an opportunity secured under letter of intent can provide additional negotiating leverage. To elaborate, if an independent sponsor waits until they have secured a transaction under letter of intent to raise funds, and the opportunity is unusually attractive, the independent sponsor will have additional leverage negotiating favorable out-of-market terms because they are representing a better-than-market opportunity.

In negotiations you will constantly hear what one side believes is “market.” What you will realize as you spend more time in this industry is that the variance surrounding structures can vary substantially. In any negotiation, always keep this in mind, and never rely on what one group or individual claims is market if it sounds suspicious or unfair. That said, there are generally three components, which listed in order of importance, are as follows:

Promote - in a transaction this is the equivalent of carried interest. At most private equity funds it is equivalent to 20%. The Limited Partnership Agreement stating how this is earned might read as follows:

First, 100% of all cash inflows to the Limited Partner ("LP") until the cumulative distributions equal the original capital invested.

Second, 100% of all cash inflows to the LP until the LP has received a preferred return on the capital invested in step 1.

Third, a "20% catch-up" to the General Partner ("GP") equivalent to 20% of the distributions realized in step 2 plus the distributions realized in this step.

Fourth, thereafter, cash flows in excess of distributions made in step 1, 2 and 3 (if any) are distributed 80% to the LP and 20% to the GP.

Promote Details:

Of the three components, the promote is probably where I have seen the greatest amount of variation. The variables to consider are as follows:

Preferred Return: In many transactions the investors are entitled to a preferred return of 8% before the independent sponsor earns a promote. The greater the preferred return, the more difficult it will be for the independent sponsor to earn a promote. It should be noted that this is also negotiable. Depending on the deal it is possible to negotiate a lower preferred return or to eliminate it entirely.

The Catch-Up: A catch up kicks in once the investors have received their capital and a preferred return (if there is one). At this stage, all dollars go to the independent sponsor until the distributions equal the promote. This can be calculated to include all dollars invested, or just the preferred return (this detail can make a significant difference). It is also not uncommon to see a catch up excluded.

Multiple Hurdles: The independent sponsor might be willing to start with a smaller promote so long as there is potential to achieve greater upside in the event of a more spectacular outcome. As an example, a independent sponsor might negotiate a 10% promote at an 8% hurdle rate so long as the fundless sponsor can earn a 30% promote if a 30% IRR is achieved (30% would be the “hurdle rate”).

There are additional variables to consider surrounding the promote (or carried interest) at a fund, but with a single transaction, those are the primary variables.

(Note: Promote, the carry and carried interest are all generally used interchangeably.)

Management Fee - At a fund this would generally be equivalent to 2% of assets under management (AUM), but for an independent sponsor the fee is hardly ever tied to AUM. Generally what you will see is a structure calling for the greater of a flat fee or some percent of earnings. It will also typically be capped. For example:

A management fee will be payable to [insert independent sponsor] in the amount of the larger of (i) $250 thousand per annum or (ii) 5% of annual EBITDA.

I provide the figures above as examples of structure, but the figures can vary considerably.

One-Time Fees - It’s not uncommon to see a closing fee included. This sum can range from $50K to $1M depending on a variety of factors. Some portion of the fee generally gets reinvested in the new entity as well. (I have seen some pretty aggressive pitches including multiple one-time fees where it starts to add up. For example, asking for a closing fee, fees for board seats, fee for a successful exit, etc.)

The challenge is that no two transactions will be alike. The independent sponsor might have strong industry expertise, or be a recent MBA graduate. The deal could be secured under LOI at a very attractive multiple, or in the midst of an auction process. The independent sponsor might be investing a considerable portion of his own net worth ("skin in the game"), or take zero risk. All of these variables will influence the outcome.