Summary Text

One of the most fundamental decisions in a deal process is whether to structure the transaction as a stock or asset purchase. We will elaborate on the pros and cons of both momentarily, but first I thought I would emphasize why this is so important. Even by the entertainment standard of private equity training materials, this topic is dry. Incentive is necessary because you could be watching raccoons steal food from cats on YouTube right now, but instead we are going to be talking about taxes.

"What is the difference between a taxidermist and a tax collector? The taxidermist takes only your skin."

-Mark Twain

"The hardest thing in the world to understand is the income tax."

-Albert Einstein

It is somewhat of a paradox that a topic so frequently discussed and reviled is generally found to be too boring to study; especially when you consider the lengths humans will go to for money. For the promise of a handsome six-figure salary straight out of college, a young twenty-something will live in a cubicle and learn to use Excel without a mouse. But comment that you can help someone grow their wealth with efficient tax structures and you’ve lost them. Fortunately, the world of efficient tax structures has its own inspirational icon, John Malone.

If you are unfamiliar with John Malone, the two most important things to know about him for the purpose of this lesson are as follows. First, he is an incredible investor:

Few people have made more money for investors over the past three decades than John Malone. The billionaire cable-TV investor and operator parlayed a small group of cable systems, originally assembled in the 1970s, into Tele-Communications Inc., before selling it to AT&T in 1999 for $48 billion.

And second, he is excellent at avoiding taxes:

No other executive in the U.S. has mastered the intricacies of the tax code to the same extent that Malone has,” says New York tax expert Robert Willens. “We are consistently in awe of the structures he and his advisors come up with to rearrange his extensive holdings, always without tax consequences, in the most advantageous way.

John Malone might not refer to it as tax “avoidance” for the term’s association with tax “evasion,” which the US government frowns on (/ will throw you in jail for). He would most likely prefer tax “deferral.” In a New Yorker interview, he explained his tax deferral logic as follows:

[Taxes are] a leakage of economic value. And, to the degree it can be deferred, you get to continue to invest that component on behalf of the government. You know, there's an old saying that the government is your partner from birth, but they don't get to come to all the meetings.

This concept is a core principal of wealth accumulation, and while it is widely accepted, it is arguably frequently overlooked. The brilliant Charlie Munger has an excellent quote on this subject that explains the math in simple terms:

Another very simple effect I very seldom see discussed either by investment managers or anybody else is the effect of taxes. If you’re going to buy something which compounds for 30 years at 15% per annum and you pay one 35% tax at the very end, the way that works out is that after taxes, you keep 13.3% per annum. In contrast, if you bought the same investment, but had to pay taxes every year of 35% out of the 15% that you earned, then your return would be 15% minus 35% of 15% or only 9.75% per year compounded. So the difference there is over 3.5%. And what 3.5% does to the numbers over long holding periods like 30 years is truly eye-opening. If you sit back for long, long stretches in great companies, you can get a huge edge from nothing but the way that income taxes work.

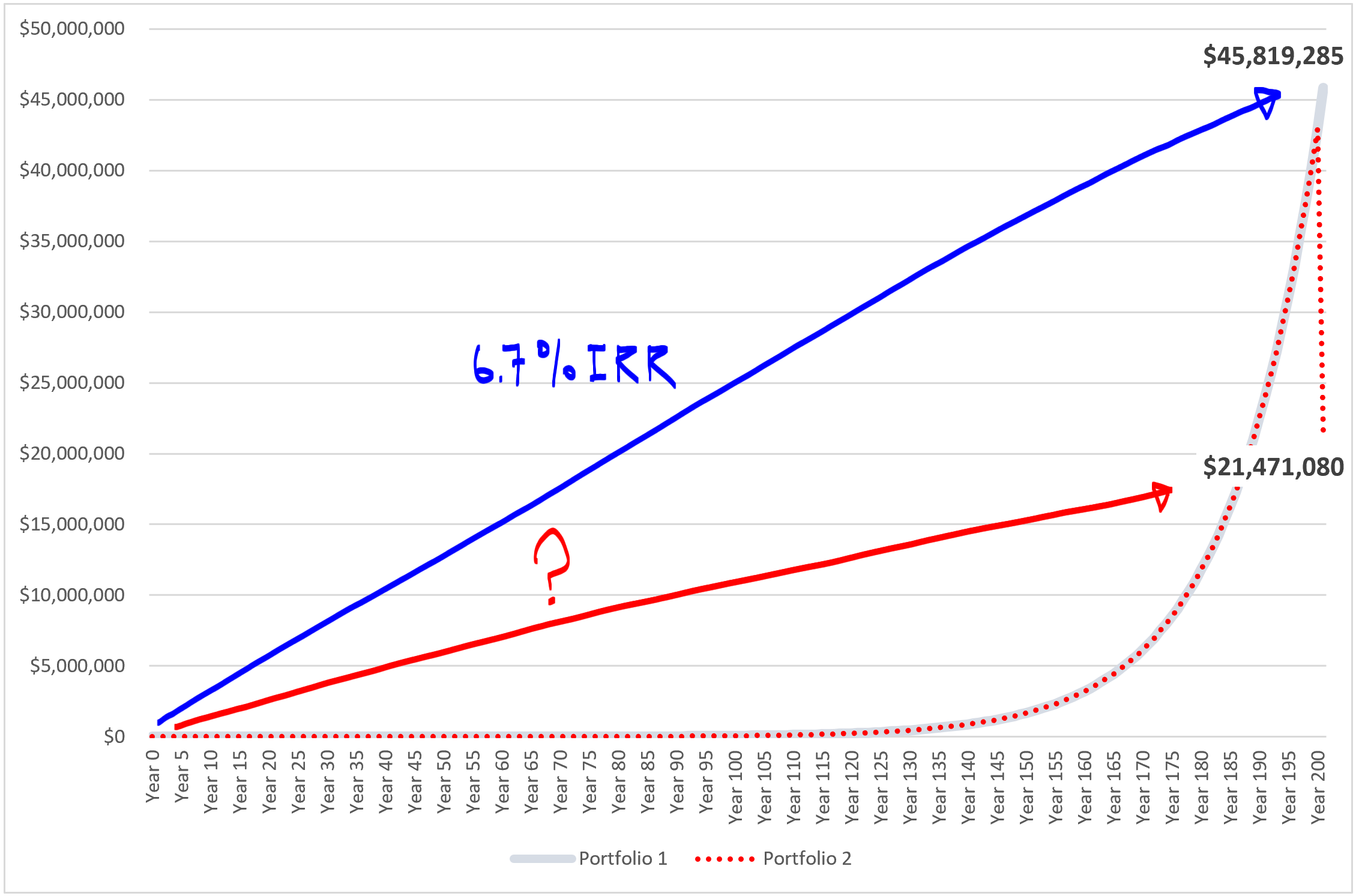

A difference of 3.5% may not sound like much, but over a 30-year period it makes a considerable difference. My favorite example on this topic comes from a thought exercise provided by Jim Grant, of Grant’s Interest Rate Observer: “Take that 200-year, 6.7% compound real return which [Jeremy Siegel, author of Stocks for the Long Run] first electrified the reading portion of Wall Street in 1994. …how would the record change if, in year 201 the market fell by 50%?”

To provide some context, if a $100 investment achieved a 6.7% compound real return for 201 years the value of that investment at the conclusion of 201 years would be approximately $46 million. So what would the 201-year compound real return be if the value dropped to approximately $21 million in year 201 instead?

The article continues:

You suspect that a 50% drawdown would play ducks and drakes with even a two-century performance record, and you confidently say so. But you are wrong: In fact, that seeming disaster would reduce it merely to 6.3%, a scant 40 basis points.

If 40 basis points did not make your head explode then you are either a human abacus or you are a human abacus. This is the power of compounding interest, and the reason tax-efficient structures and investment practices are deserving of your attention.

If I have failed to gain your interest, the last carrot I can offer is that this is likely to come up in an interview, and acting like this stuff gets you excited will help land you that cubicle residence.

"The avoidance of taxes is the only intellectual pursuit that carries any reward."

- John Maynard Keynes

Stock vs. Asset Purchase

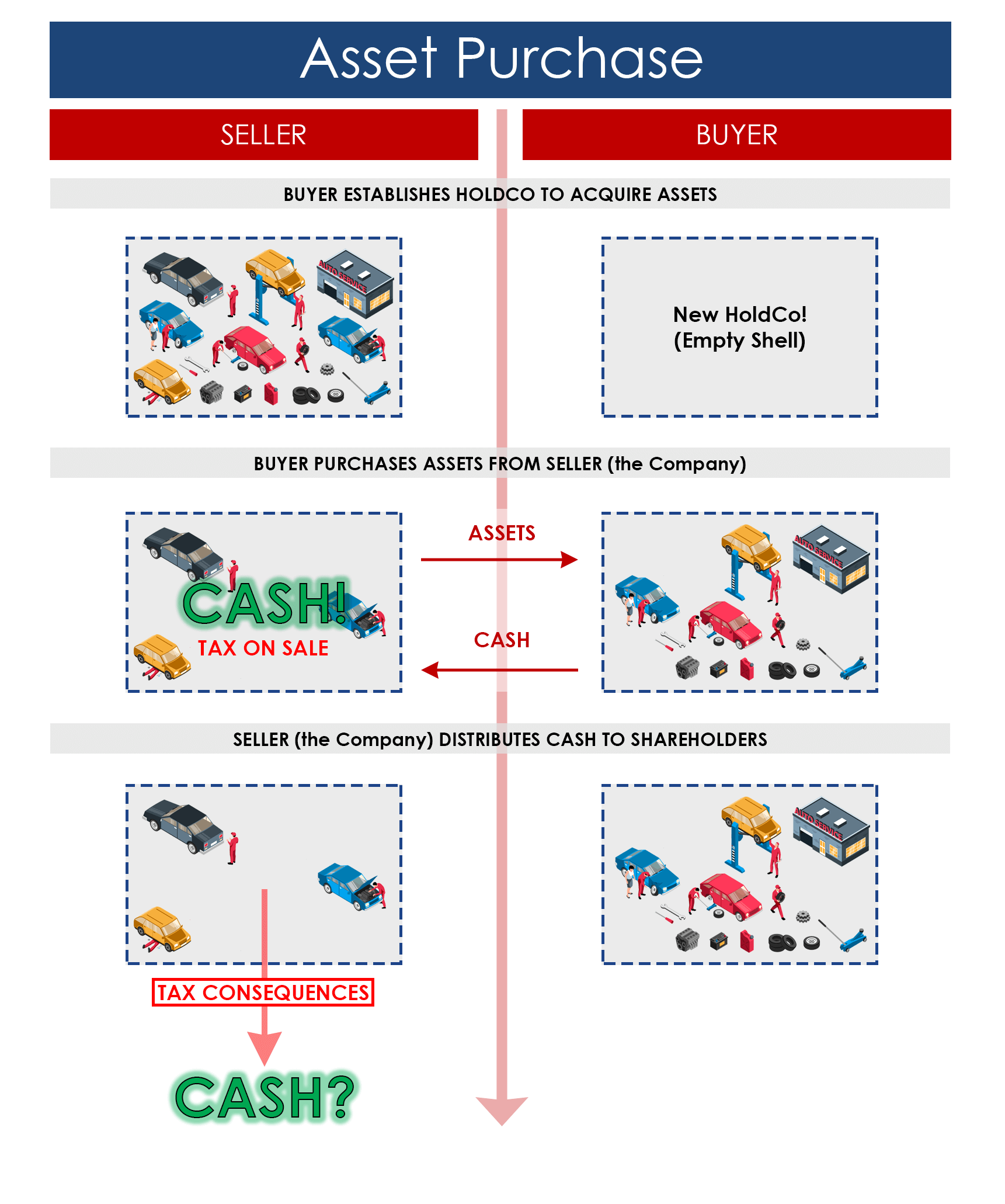

The scintillating tax banter was just the icing on the cake to lure you in. Additional pros and cons exist between the two, and we will explore those sufficiently in this lesson. To help visualize an otherwise abstract concept, think about there being two baskets when a transaction closes. One basket will contain what remains with the seller, and the other basket will contain the property transferred to the buyer.

In a stock deal everything transfers to the buyer. When you purchase 100% of the common stock of a company, you assume everything associated with the business. All of the company’s assets and its liabilities transfer to the buyer’s basket.

In an asset deal, on the other hand, the buyer purchases assets from the business entity. So the business entity remains with the seller, and only the assets and liabilities outlined in the purchase agreement transfer to the buyer’s basket. Between the two transactions, there are two primary variables to consider:

- The Tax Consequences of the Transaction

- The Liabilities of the Target Company

To address the tax variable properly requires adopting both the seller’s perspective and the buyer’s perspective for each topic. We will then conclude this analysis with commentary on the liabilities of the target company.

Please download the PDF notes for the full lesson.